At a Glance: Building a 100% Clean Electric Power Grid

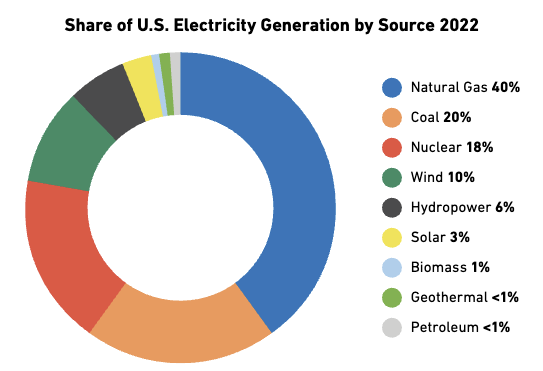

Converting to zero-emissions electricity while dramatically increasing output is an essential step in building a clean economy. Electricity generation is the second largest source of greenhouse gases in the U.S., accounting for 25% of annual emissions. Converting to 100% clean power is necessary to eliminate those emissions; increasing overall production is needed to support the electrification of nearly the entire economy. The national mission for clean power will:

Transition electricity production to 100% clean sources in 10 years by financing and coordinating investments in clean energy, instituting a Clean Energy Standard (CES), and radically reforming the siting and permitting process for power production and transmission projects.

Increase total energy production by at least 100% to accommodate electrification of the general economy as well as power-hungry applications such as CO2 drawdown and hydrogen production.

Build new high voltage, long-distance power lines to provide affordable power to population centers while eliminating bottlenecks and shortages during demand peaks.

Make energy storage capacity ubiquitous at every level of the nation's electricity infrastructure from power plants to homes and consumer appliances.

Expand distributed power generation solutions such as commercial and residential rooftop solar and ground-source heat pumps.

Upgrade the nation's power grid and utilities to accommodate massively increased demand for electricity.

The United States is already in the midst of a clean energy boom. Billions of dollars have been invested in clean energy projects over just the last few years. Despite this progress, the United States is not on track to reach 100% clean power within the next decade — or even by 2050.

A range of obstacles is holding back America's transition to clean power despite the economic advantages of clean power. These include a prohibitive, slow and redundant regulatory system, backwards incentives and inadequate planning and investment at utility companies, failed attempts to engineer electricity markets, and more. Our plan contains measures for addressing all of these.

The key mechanism for driving the country to 100% clean power is the Clean Energy Standard (CES), administered by the Department of Energy and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which requires that utilities replace all fossil-fuel power sources with clean power in 10 years.

The policies introduced in this national mission will do more than build a clean energy grid. This national mission will create high-paying jobs for workers across multiple industries including utilities, manufacturing, energy development, and R&D firms. The energy transition also gives America an opportunity to rectify some of the injustices the current energy system has placed on low income and marginalized communities.

Introduction

This is a national mission to build large quantities of new clean electricity generation and storage capacity, transition the U.S. power grid to 100% clean power by 2035, and to double the size of the U.S. power grid. This mission calls for large investments in domestic clean energy manufacturing capacity so that the U.S. can supply its own needs and join the ranks of clean energy technology exporting nations. In conjunction with the rest of the Mission for America, by 2035, wind and solar power equipment will be manufactured with minimal embedded greenhouse gas emissions, and will therefore fill a high-value niche in the global economy. The Clean Power Mission also calls for a new nuclear program, which is detailed in its own chapter. The objectives of this national mission include reaching zero emissions in U.S. electricity production as fast as possible, speeding the global transition to net zero by exporting clean power and transmission technologies, increasing national wealth, and creating as many new good jobs as possible for American workers.

The mechanisms to accomplish this mission include: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which will provide investments, guarantees, and deal making; a Clean Energy Standard that will require utilities to use 100% clean power by 2035; bold presidential leadership to rally the nation behind this mission and break the stranglehold of a dysfunctional electric regulatory regime; and legislation to accelerate the manufacturing and deployment of clean power technologies.

This mission is unique among clean power plans in its short timeline, reliance on exceptional presidential leadership, rejection of point source carbon capture, insistence on nuclear power as being practical and necessary, emphasis on investing in domestic clean power manufacturing, and use of a new national investment institution — the Reconstruction Finance Corporation — which was introduced previously in its own chapter.

We expect skeptics to insist that it is not necessary to get to 100% clean power in 10 years, let alone to additionally double or triple the quantity of clean power production. But the planet gets warmer with every ton of CO2 emitted by power plants. Today’s models predict that even the most aggressive emissions cuts will still see the planet warming to dangerous levels. Every opportunity to further cut emissions must be taken and there is no excuse for the richest, most technically advanced nation on earth not to move as fast as physically and organizationally possible.

Decades ago, when we had far less advanced technology, a smaller economy and a smaller population, we built new power generation and transmission capacity at an even faster rate than is needed now to achieve this goal.1 Critics will argue that our society has devolved into a rudderless nation incapable of building as quickly as it once could. To that, we respond that one of the central purposes of the Mission for America is to resuscitate our national culture back to one that can build again.

Moreover, this mission is designed, as with the other missions in this plan, to make accomplishing it a multiplier of national income, wealth, and general economic and social capacity rather than a subtraction. Upgrading our energy infrastructure is not a burden that we will benefit from stretching over as long a period as possible; it is one more means to reinvigorate our economy and society — the faster we move, the more we will save and earn.

This chapter includes a brief explanation of some of the key functional principles of America’s power grid, as well as of how the current grid and its management fall short.

Context

The following section is intended to give readers the background information necessary to grasp the major problems the nation faces in getting to 100% clean power, as well as the solutions we lay out in the final section of this chapter.

The Goal Defined

The primary goal of this mission is to get the U.S. to 100% clean power by 2035. The mission has a number of additional goals that we specify either because they are necessary to achieve the primary goal or because they are necessary to ensure that the primary goal is achieved in a way that supports the comprehensive Mission for America: ensuring that the switch to clean power is accomplished in a way that builds the nation’s overall capacities and wealth instead of depleting them.

The specific goals of this national mission are to:

Retire all of America’s more than 3,400 fossil fuel-burning power plants by 2035.2

Build new clean electric power generation capacity — not only to replace decommissioned fossil fuel plants, but also to provide enough additional energy to power the nation’s post-transition economy — which may require doubling the size of the power grid.

Reset the primary objective of federal energy regulations to that of creating a stable, reliable, and 100% clean power grid.

Build adequate additional long-distance, high-voltage power transmission lines to create a truly national grid that can move power in required quantities to where it is needed.

Build adequate short-distance transmission capacity to accommodate new power generation sources and higher levels of power demand, from both commercial and residential users.

Develop and deploy next-generation energy technologies such as small modular nuclear reactors and enhanced geothermal energy.

Scale up domestic wind and solar industries, to ensure energy independence, to earn export income, and to provide good jobs for American workers.

Build small and large-scale storage capacity to create a stable and reliable grid that will include large quantities of intermittent renewable power sources.

Achieving these goals will require a sweeping mobilization of the nation’s people, companies, and resources. It will also require shifts in public sentiment to allow support for a new nuclear power program, and to make it unacceptable for politically motivated actors to block needed renewable power generation and transmission projects.

While it is impossible to predict exactly what quantity of electric power will be needed after the full transition away from fossil fuels, we do know that it will be a multiple of our current electric power generation, meaning that we will at least need to double our total power production. This is achievable because the process of decarbonization will lead to so many more things will be powered by electricity, either directly or indirectly, through fuels created using electricity — including heating, air conditioning, appliances in homes and buildings, vehicles, ships, airplanes, manufacturing and chemical factories, and some share of the carbon sequestration required by all the modeled scenarios that keep the planet below a catastrophic level of warming.3

What’s Unique About This Mission

This national mission differs from other plans for getting to 100% clean power in several respects:

It’s timeline is ambitious but achievable. We believe that as the catastrophic effects of global warming become harder to ignore, and as more aggressive solutions are elaborated, the mainstream position will continue to shift toward comprehensive plans to reach net-zero emissions as fast as is physically and organizationally possible. We believe that, in this context, a 10-year timeline for reaching 100% clean power generation is a reasonable target, and we will attempt to show why that is so in this chapter.

These targets are ambitious, yet we believe they are appropriate for the present moment. Over just the last several years, the Democratic Party and mainstream environmental organizations went from having no specific target date for eliminating fossil fuels in power generation to passing legislation that aims to reduce emissions by 50% in just five years.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton ran for president with almost no climate policy at all. When it came to clean power, Clinton proposed cutting emissions by more than 80% by 2050 relative to 2005 levels.4 That same year, Bernie Sanders, running partly on a promise to act on climate change, proposed an 80% reduction in emissions from 1990 levels by 2050.5

Then suddenly there was a change: when the 2020 presidential primaries first began in 2018, the Democratic candidates had much bolder proposals. Sanders now called for the Green New Deal with 100% renewable energy by 2030.6 Joe Biden proposed to cut emissions from power generation by 100% by 2035, and has since committed to reducing U.S. emissions to 50% of 2005 levels by 2030, creating a 100% carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035, and achieving a net-zero economy by 2050.7

Despite the many climate deniers, critics, and challengers to a timely and complete transition to clean energy in 10 years, economists and climate scientists have shown that such a transition is possible, though incredibly difficult.8 History, including recent U.S. history, is full of examples of seemingly impossible tasks being completed much faster than anyone thought possible. Often, when there is a will, there is a way. When we are faced with such extreme consequences for moving too slow, we should make plans to move as fast as we think might be possible. Even if we ultimately fail to complete the transition in 10 years, aiming for 10 years will speed up the process to the quickest transition possible.

Moreover, this mission, in combination with all the other national missions in this proposal, is not an expense or a draw on U.S. human or financial capital. If executed as we recommend, it will actually be a multiplier of U.S. capital. For example, by building export industries in the clean power sector, we will earn additional national income and cut down on national expenses in the long run, which will allow the country to do more, not less.

It is a comprehensive plan that includes a full set of policies to get the country to 100% clean power. Most plans include a number of policies designed to encourage the adoption of clean power generation, but do not go so far as to require that 100% clean power is achieved. Some, including those with Clean Energy Standards, may mandate that a state or the country as a whole reach 100% clean power by a future date (e.g., 2050), but they lack a full set of policies to achieve that goal. These plans generally hope that energy markets and investors will respond to the mandated goal or to incentives by doing all the work that is necessary to achieve the goal — despite the fact that many such goals are missed, and many incentive packages do not elicit the desired response.

Our plan proposes a new public financing and deal-making institution that will be capable of providing adequate investment capital and of arranging deals to launch companies and even entire industries. The Mission for America requires that the U.S. begin to restore its public financing and economic restructuring institutions, starting by creating a Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), described in depth in its own chapter. On their own, mandates and incentives are not enough to reach 100% clean power; to get to 100% will require a greater quantity of capital and coordination than private markets are currently able to provide.

Our plan provides adequate financing and assistance for America’s 3,000 utilities to enable them to get to 100% clean power. Merely requiring utilities to convert to clean power is insufficient to achieve the goal; most utilities are very small and will need both capital and technical assistance to go all the way to 100% clean power. Our plan includes a new program within the Reconstruction Finance Corporation that will help finance and assist utilities as they undertake intensive upgrades to the American power grid.

Our plan calls for a national mobilization to build a new nuclear program. Many other plans shy away from requiring a nuclear program because of controversies around cost and safety. Our plan accepts that to get to 100% clean power, we need large quantities of consistent clean baseload power that runs 24/7, and that nuclear power is a safe and feasible option for this. Currently, problems surrounding the cost of building new nuclear capacity can be overcome by building a new nuclear program that creates new nuclear capacity at scale. If the U.S., as well as far less wealthy and advanced countries, could do it in the 1960s and 1970s, we can create a safe and cost-effective nuclear program today.

A push to revive America’s nuclear energy industry will be such a controversial and difficult undertaking that we have decided to give it its own future national mission within the Mission for America. However, in a later section of this chapter we make the case for why nuclear is a necessary, safe, and practical part of the solution to meet America’s energy needs.

It builds on the success of the Biden agenda. When President Biden entered office, he surprised many on the left by actually attempting to follow through on his promises. Among the various pieces of legislation already passed by Congress under Biden, the most important are the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). These are all great down payments towards a transition to a net-zero economy. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which provides $369 billion towards climate and clean energy provisions, is the most significant investment to curb total carbon emissions: up to 40% by 2030 according to a Senate Democrats summary.9

However, these new laws and investments must be followed through to ensure that their full economic and climate benefits are realized. Since the passage of the IRA, both the public and private sector have been hard at work implementing its provisions. It is paramount that these investments reach their maximum potential in addressing the issues they are designed for as well as continuing the push towards a clean and just economy by addressing the many other issues we are facing.

This incredible progress was accomplished by a combination of creative and powerful activism, bold choices by a few key Democratic Party leaders, and the reality of devastating climate change manifesting in bigger and more terrible ways each year. The National Mission for 100% Clean Power seeks to push the goal further to the elimination of all fossil fuels from power generation as fast as is physically and economically possible.

Our plan aims to reform the entire clean energy deployment process. Many progressive climate plans have been laser-focused on bringing down the cost of clean power generation relative to fossil fuels and creating financial & consumer incentives for clean power adoption. Bringing down relative costs and encouraging the adoption of clean technology is an important part of the transition away from fossil fuels, but it is only one part of the process. Regulatory, political, and capacity issues will continue to plague clean energy deployment long after clean energy becomes significantly cheaper than fossil fuels. Each of those issues endangers our ability to deploy enough clean energy at the necessary scale. Our plan aims to combine the necessary financial investments with the building of new national state capacity and institutions to ensure that clean energy can be deployed.

Why We Must Move Quickly

As with most parts of the Mission for America, we recommend moving at a faster pace than other proposals. The primary reason for this is consistent with other missions: the crisis is too great to wait, and the opportunity is too big to put off.

Because of the terrible urgency of global warming, the whole world needs to reduce every segment of emissions as fast as is physically possible. Emissions from U.S. energy production are one of the world’s biggest single sources of emissions.10 It doesn’t matter that it is “only” 25% of America’s 15% of global emissions.11 Energy production is one of the major sources of emissions that must be ended immediately to prevent catastrophic global warming. Some nations are in a better position to do that now than others. It is unconscionable for those nations to say that they will wait for the slowest nations to act. It makes sense that the richest, most industrialized, and most technologically advanced nations in the world will need to move disproportionately faster and achieve disproportionately more than other nations to slow global warming as much as possible, as quickly as possible. The United States, being the richest, most technologically advanced country in the world, with the largest industrial base, must expect to go the fastest and to do the most.

At the same time, by taking the lead and being the first large country to comprehensively and rapidly get to zero emissions from energy production, the U.S. can both accelerate the global transition, and profit from it. By following the plans recommended here, the U.S. will develop many lucrative industries that can provide materials, technology, services and consulting to the rest of the world as it transitions away from fossil fuels. The final result will be a more prosperous U.S. and a faster global transition away from fossil fuels.

As covered in the introductory chapters, the entire Mission for America is designed not only to reduce U.S. emissions but to contribute to the gargantuan task of the transition to a net-zero global economy. In the case of clean power, the U.S. will make several major contributions under this plan:

Supply the equipment, materials, and management and consulting services to build long-distance high-voltage DC power lines.

Supply the materials, technology, and management and consulting services to upgrade utility companies to be able to handle the electrical upgrade of the entire national economy.

Supply the equipment, materials, and management and consulting services for clean energy.

Build nuclear power plants, and provide management services and security for them.

Pioneer next generation energy storage technologies that can be sold and deployed around the world.

Why This Goal Is Possible

Some say that it’s not possible to act as fast on the energy transition as this mission proposes. They say that America’s regulatory, zoning and approval processes make it impossible to build new power projects or transmission lines as fast as we propose; that government cannot afford the investments that private finance will not cover; that the technology doesn’t exist yet to provide 100% clean power without a fossil fuel baseload; and that it’s not possible or would be too expensive to build nuclear power generation capacity to provide the needed baseload and additional power generation capacity. We will answer each of these objections in turn.

Regulatory obstacles will prevent slow new infrastructure. Saying that we can’t build world-saving infrastructure because of regulatory problems is like a man saying that he can’t start exercising because long ago he promised himself he’d never be a person who goes to the gym. Or, that it would be too difficult for the government to launch a widespread vaccination campaign only a year after the outbreak of a global pandemic. We are not a stagnant society when it comes to many areas of our economy and life, and there is no reason why we need to resign ourselves to stagnation in the area of power generation and transmission. In fact, it is hard to think of an industrial transformation that would have less of a perceived inconvenience on people’s lives than replacing fossil fuel power generation with clean power and building new power transmission lines. In recent decades, our society has accomplished sweeping regulatory changes under both parties that radically changed how people receive and use some of the most important economic products and services in our lives: auto emissions regulations; the break up of telephone monopolies; the rise of mobile phones and subsequent rollouts of new frequencies and technologies for them to operate on; big changes to the regulation of food production and preparation; major changes to traffic regulations and their enforcement; a significant overhaul to the health insurance industry under the Affordable Care Act; constant changes to the tax codes which everyone who files taxes must laboriously keep up with. This list could go on and on.

What is so sacred about the way we currently approve new power plants and new transmission projects that we as a society cannot change it? The simple answer is that every change to how we organize our society is a struggle, and, unfortunately, the forces on the side of building more clean power and transmission have simply been weaker — or perhaps simply less bold and determined — than the forces organizing to stop them. It’s true that the current regulatory system makes it much easier to stop a project than to get one approved. That system has to change. This mission details sweeping reforms that can be passed by a Congress assisted by bold leadership from a president and pushed by forceful lobbying from clean power industries, investors and activists. But even after those reforms, clean power advocates will need to find a way to fight and win against powerful and entrenched interests that oppose change. It will be up to the president who launches the Mission for America to inspire clean power advocates to do so and, in so doing, to tip the political and cultural playing field in their favor.

The government can’t afford it. As the nation and the world switch from fossil fuels to clean power, new profit-making operations will be launched to generate and transmit power, and to provide countless other products and services needed for the transition. If private capital was willing or able to organize the huge investments and deals required to make the transition happen on the timetable required by global warming, it would be doing so already. Instead, it is necessary that the government play the role of investor and dealmaker of last resort. Our government today does not have an institution for that purpose. The Mission for America calls for one to be created in the form of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which is detailed in its own chapter. Though these investments require some outlay of public capital, our government is more than capable of raising these funds, which will become streams of income the moment the investments begin returning profits.

The technology doesn’t exist yet. Almost all of the technology needed to produce and distribute clean power is many decades old. The United States has used solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, and nuclear technologies for decades. Some technologies, such as utility scale energy storage, are newer but have experienced accelerated growth in a short period of time. There are also many technologies on the brink of commercialization and widespread adoption, such as enhanced geothermal or hydrogen energy storage, that will further enable a 100% clean energy grid.

Nuclear power is no longer viable. Building out additional nuclear capacity is very much possible. We will give this subject brief coverage in this chapter, and much fuller coverage in a later chapter that lays out our proposed National Mission for Nuclear Power.

How the U.S. Power Grid Is Managed

Nearly everywhere in the world, the power grids in a given area are run by a single entity with a monopoly on power delivery. In economics, power delivery is what’s known as a “natural monopoly” because the most efficient number of companies to have in the power delivery market is always one.12 This is due to the practical reality that it doesn’t make sense to have multiple companies all running their own parallel sets of power lines next to each other from generators to homes.

In some countries, power is delivered by state-owned monopolies, and, in others, by private companies which are usually heavily regulated by the state. The U.S. falls into the latter category. Electrical utilities in the U.S. fall into three categories:

Private investor-owned utilities (IOUs)

Publicly-owned utilities, usually owned by municipalities (POUs)

Cooperatively-owned utilities, i.e. owned by customers.

All are regulated directly by the states in which they operate, and all are monopoly providers.

The 168 investor-owned utilities serve 72% of American consumers.13 The rest are served by 1,958 publicly-owned utilities, mostly owned by small cities and towns, and 812 cooperatives, mostly in rural areas.14

Up until the 1970’s, most utilities tended to be fully vertically integrated monopolies that controlled both production and distribution of power.15 In other words, utilities owned the power plants, the power lines, and all the other infrastructure involved in the production, distribution, and consumption of electricity. They made all the short-term decisions about which plants should be operating and at what levels in order to keep the power flowing smoothly. And they made the long-term decisions about when and where to build new power plants and transmission lines. They sent customers their bills and set their rates and other policies. Utilities were not isolated islands; they were connected to each other by power lines, forming a patchwork national grid, and utilities often contracted with each other to share power.

Almost since the advent of electricity in America, utilities have been directly regulated by states. But the federal government quickly began to weigh in too. Today, the federal government sets high-level policies that determine the rules within which states and utilities operate through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).16 The FERC is a bipartisan commission whose five members are presidential appointees, with a rule that no party can have more than three members.17

In recent decades, federal policymakers and FERC commissioners from both parties have pushed for a more market-based approach to power delivery. Though nothing can be done about the monopolistic nature of power lines, the FERC has tried to introduce market forces into electricity production and consumption, with utilities being required to open their networks for use by private producers, and, in some areas, giving consumers a choice about which power providers to pay. Because of the need to precisely control the amount of power entering the grid from minute to minute, however, these efforts have created elaborate farces in which power producers and grid operators essentially playact as market participants. To deliver power reliably, these marketplaces must be so jerry-rigged that they are deeply inefficient. These inefficiencies have often led to short-term disruptions in power delivery, poor long-term planning, and corruption.

Because these new electricity markets were not created through the interplay of supply and demand, but, rather, through abstract negotiations between policymakers and energy lobbyists, they are full of perverse incentives. For example, according to FERC rules, utilities must buy electricity from producers at a uniform price from minute to minute.18 This prevents utilities from negotiating lower prices from wind producers when the wind is blowing hard, or from offering other producers a higher price to keep them operating in anticipation of a coming demand spike.19 Other artificial restrictions on the market have allowed companies to manipulate prices to make huge speculative profits while disrupting energy delivery and costing rate payers huge amounts of money.

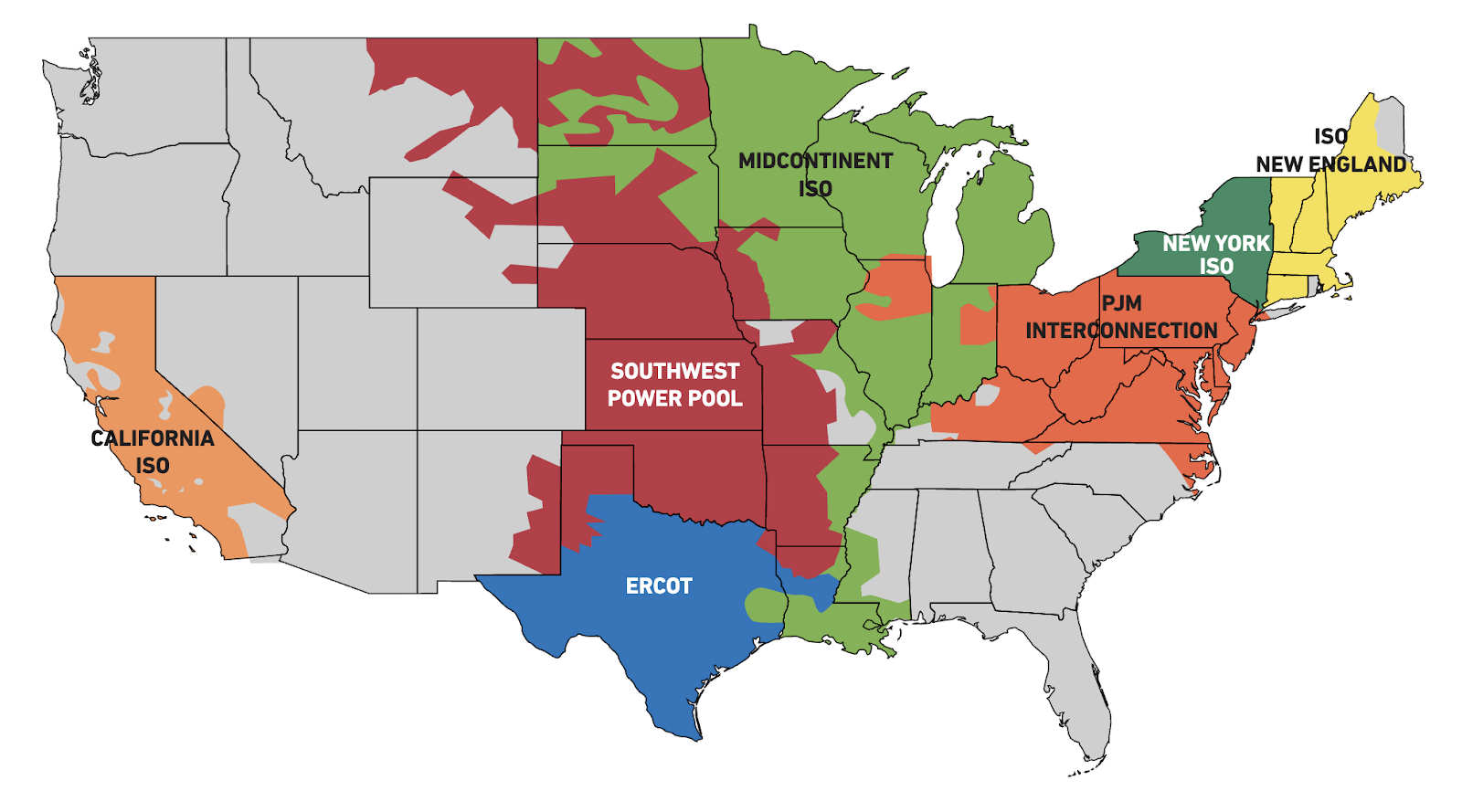

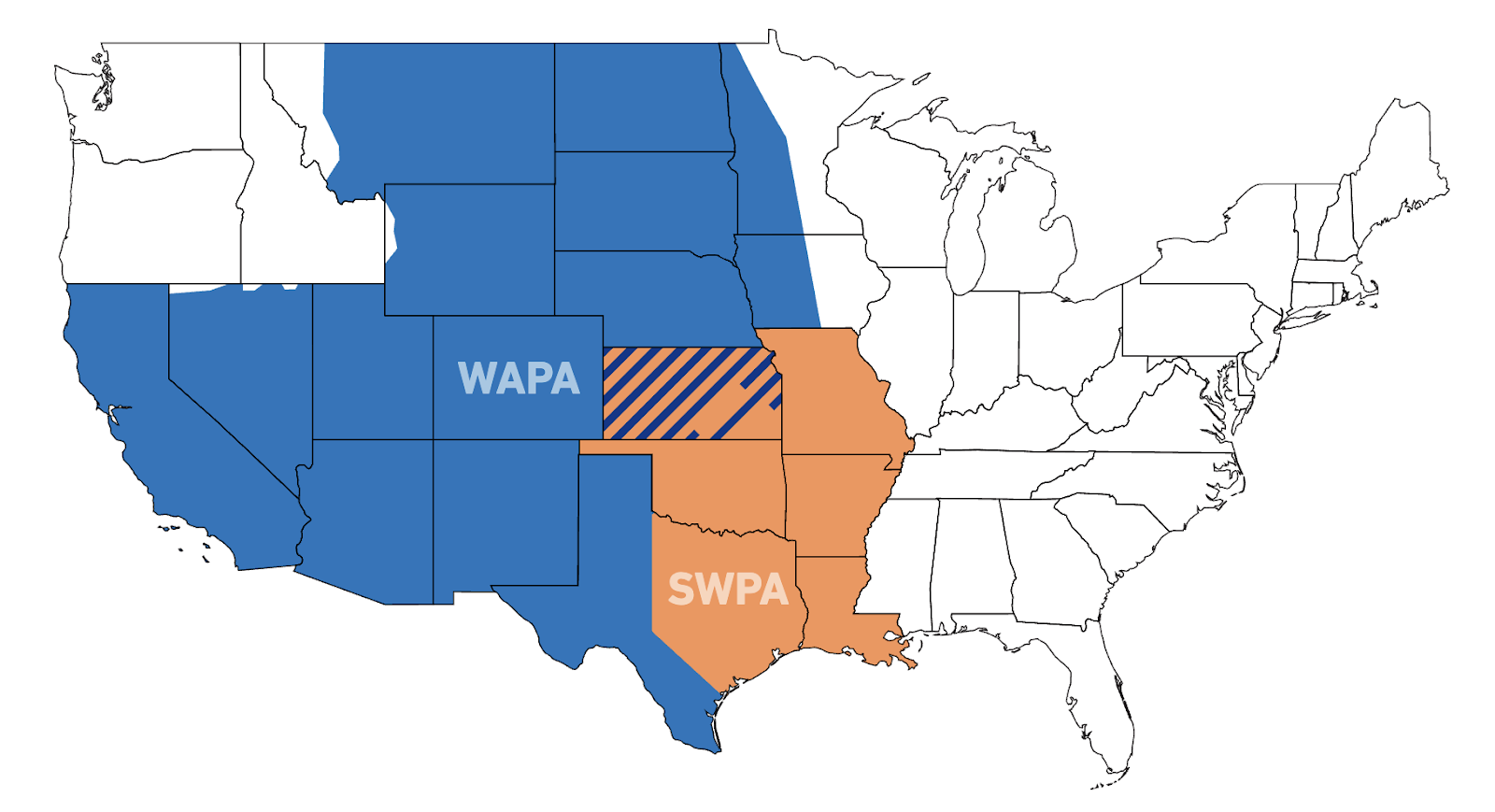

To create these contrived marketplaces, the FERC called for the creation of Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) — called Independent System Operators (ISOs) when operating inside a single state — to oversee the new power markets in which utilities, producers, and transmission operators would interact.20

Today the short- and long-term decisions that determine the operation, growth and maintenance of the U.S. grid are made by many overlapping and often conflicting groups of people and organizations spanning all levels of government, the RTOs and ISOs, local and state utilities, private producer and transmission companies, as well as various environmental and citizen review organizations.

The Critical Problem of Intermittency

Solar, wind, and even hydroelectric power come with one critical drawback: intermittency. Sometimes the wind doesn’t blow. Sometimes thick clouds block the sun. Sometimes water levels in rivers are too low to power hydroelectric generators. An energy source’s reliability is often measured by its “capacity factor,” meaning how often it operates at max capacity.21 The capacity factor of wind and solar is 34.8% and 24.5% respectively.22 If 100% of our power generation was renewable then, even if we had much more than we needed under normal conditions, there would still be times when there would not be enough energy generated to power society.23 Even if those days or weeks were rare, they could be catastrophic. This problem is the main legitimate argument against transitioning to 100% renewables.

Many renewable energy advocates dismiss fears of intermittency as overblown. They may be right, but it is difficult to know for sure across all scenarios, and the risk should be taken seriously. Reassuring Americans that this transition can be accomplished without the risk of blackouts is key to convincing our whole society that switching to 100% clean power is possible and will be beneficial for all.

Thankfully, there are many solutions to intermittency, including storage, long-distance transmission, and adding more energy generation sources that are not “renewable” but are “clean,” such as nuclear power, to provide clean, reliable baseload. Energy storage allows energy to keep flowing even when power generation dips below what’s needed. Transmission allows power to flow into a region that lacks adequate sun and wind from regions with plenty. Nuclear reactors can provide consistent “baseload” power to the grid, and in the comprehensive Mission for America, will power carbon sequestration, hydrogen production, and other processes even when they are not needed for baseload. We deal with each of these solutions to the intermittency problem in the following three sections.

The Role of Storage in the Energy Transition

Widespread energy storage deployment is essential for a 100% clean energy future. These technologies bolster grid flexibility, capturing excess renewable power during peak periods and releasing it during generation downtimes or high-demand moments.

Energy storage has unique benefits relative to other strategies to mitigate intermittency. Energy storage is much faster to build than either nuclear and long-distance transmission infrastructure, both of which are subject to long permitting processes and strict regulations. The average build time for a utility-scale storage facility is only a couple of years, whereas long distance transmission lines often take 10 years to complete, and new nuclear sites take a global average of 7 years to construct and typically about 10-15 years to finish in the U.S.24

Moreover, when it comes to cost, storage facilities also have a competitive edge.25 The largest energy storage facility in America, Moss Landing Energy Storage, cost around $500 million to build.26 Distributed energy storage available to homeowners and businesses, such as the Tesla wall battery, fill a unique role that can’t be replicated by either transmission or traditional nuclear plants. Transmission and nuclear energy are also essential components of the energy transition, but they have more specialized use cases than energy storage, the latter of which can be more widely and efficiently deployed on a faster timeline.

Energy storage is also a key tool in preventing blackouts during weather crises. Energy demand can spike far beyond generation during severe weather events such as heat waves or freezes, endangering grid stability when people need it the most. The energy stored in batteries or other storage systems can be called upon during these demand spikes to supply power and keep the grid from failing. The potential of batteries to store excess power and then supply it when needed was demonstrated in the September 2022 heatwave in California. California’s batteries provided more power during the critical period of peak demand than Diablo Canyon, the state’s largest power plant.27

The growing deployment of energy storage technology underscores its recognized importance in the energy transition.By the end of 2020, the United States had installed around 1,650 MW of utility-scale energy storage capacity — three times as much as by the end of 2015.28 In 2021, utility-scale battery storage capacity nearly tripled from 2020 capacity to roughly 4,630 MW.29 In 2022, the U.S. added 4,800 MW of new utility-scale battery storage capacity.30 Small-scale storage capacity, made up of the type of batteries used to power residential or commercial spaces, is also a growing market, with 400 MW of capacity installed by the end of 2019.31 Residential storage amounted to about 436 MW by the end of 2021.32 The rapid growth of the energy storage industry is inspiring, but the rate of deployment is still far below what is needed to sustain a 100% clean energy economy.

Energy storage solutions can be broadly classified into three categories: short-duration, long-duration, and seasonal. These categories reflect how much and how long a technology can store energy. Different situations will require the use of different types and durations of energy storage. We will briefly discuss each category and the role they play in the energy transition.

Short-duration energy storage is any storage method capable of discharging power for up to 10 hours. The predominant form of short duration energy storage is lithium-ion batteries. Short-duration energy storage is already commonly deployed on the grid. The benefits of short-duration energy storage have been convincingly demonstrated in recent years. The storage that kept California operating during the September 2022 heatwave was mostly batteries designed to provide up to four hours of power during daily periods of peak demand.

The second type of storage necessary to support the transition to clean energy is long-duration energy storage (LDES). Long-duration energy storage is defined as any energy storage system which would provide 10 hours or more of power. However, there are many new technologies competing to provide LDES – some of which are detailed later in this section. A recent McKinsey report found that LDES deployment could mitigate the equivalent of 10-15% of America’s electricity sector emissions.33 The same study estimated that “10% of all electricity generated would be stored in LDES at some point” and that LDES can reduce the cost of decarbonizing the U.S. power system by $35 billion annually.34

The third type of storage is seasonal storage. U.S. energy consumption peaks in the winter due to heating demand, and during the summer due to cooling demand. Currently, seasonal energy fluctuations are addressed with fossil-fuel-powered “peaker” plants that are only used during periods of peak energy demand. These plants can be assured to be available when needed in part because the U.S. currently stores large amounts of fossil fuels for this purpose, including large amounts of natural gas stored in underground caverns. If the United States wants to entirely phase out fossil fuels, then it will need to develop similar seasonal storage capabilities that run on clean energy. There are a variety of different storage techniques that could fill this role, but most are still in their infancy and not widely deployed. The best option for the seasonal storage of renewable energy in the U.S. is to use renewable energy to produce green hydrogen which is then stored in underground salt caverns. The benefits of using hydrogen for seasonal storage, along with other alternatives, will be discussed later in this section.

This national mission will rely on an “all of the above” strategy, using whatever storage method is best suited for a particular geography and energy market in order to maximize energy storage capacity. Most of our policies are designed to apply universally to all forms of energy storage, though a few do focus exclusively on one technology.

Given the variety of energy storage our policies address, it’s crucial to grasp the nuances of the key technologies. The rest of this section will be dedicated to analyzing some of the most significant forms of energy storage and the role they may play in the transition to 100% clean energy. We analyze two already common energy storage technologies (lithium-ion batteries and pumped storage hydropower), three up and coming technologies (flow batteries, electric vehicles as energy storage, and green hydrogen), and one technology still in development (molten-salt batteries).

Pumped Storage Hydropower

Pumped storage hydropower (PSH) is the most widely deployed form of energy storage in America. There are 43 active PSH plants in the U.S., comprising 93% of America’s utility-scale storage capacity.35 PSH works by moving water between two different water reservoirs at different elevations. Water in the higher reservoir is moved down to the lower reservoir through a system of tubes and produces electricity by turning a turbine within those tubes.36 The amount of energy stored in a PSH facility is dependent on both the natural terrain of the site and on local weather conditions, such as rainfall and droughts. Larger PSH facilities can function as LDES and provide up to 16 hours of power.37

The main impediment to expanding America’s PSH is geographic. Unlike batteries, which can be mass-produced in a factory and then deployed almost anywhere, PSH has to be co-located with large bodies of water. Unfortunately, this constrains new PSH to a few limited areas. Further complications arise when considering the potential impact that PSH facilities may have on the local environment and community. Creating reservoirs and dams for PSH facilities can negatively impact aquatic life,

local agriculture, and important tribal locations.38 All of these concerns further narrow the list of potential PSH locations. Despite these limitations, there are some opportunities to expand PSH capacity. A 2016 DOE study found that there is the potential to increase America’s PSH capacity by 36 GW between now and 2050.39 A more recent study from the Water Power Technologies Office within the DOE identified over 11,000 sites in the contiguous United States where PSH could be deployed.40

Lithium-ion Batteries

Lithium-ion batteries are by far the most common form of battery powered energy storage in the United States.41 The explosive growth of the lithium-ion battery industry has been driven primarily by declining costs and increasing interest from private investors. Lithium-ion batteries can be built to accommodate a variety of different applications, ranging from small-scale storage for homeowners to large utility-scale storage.

This adaptability has made small-scale batteries, such as those serving single homes or buildings, increasingly attractive to home and business owners. As of 2022, there is around 450 MWs of small-scale battery storage deployed in the United States.42 The primary driver of small-scale battery storage adoption is fear of blackouts from grid failures and natural disasters. As a result, most small-scale battery storage is located in states with a history of grid failures such as California and Texas.43 Policymakers will need to find ways to encourage consumer adoption outside of these specific circumstances so that the benefits of home battery systems can be felt across the nation.

Lithium-ion batteries have been even more successful as a source of utility-scale energy storage. The average utility-scale lithium-ion battery can provide power for four hours, though some newer batteries have slightly longer durations. Developers have compensated for the short duration of lithium-ion batteries by building as many batteries at one site as the local geography allows.44

The rise in deployment is primarily due to the price of battery packs sharply declining in recent years. The costs of lithium-ion battery packs declined from $1200 per kWh in 2010 to $132 per kWh in 2021,

an astounding drop in price of 89%.45 The price did increase briefly in 2022, but this is primarily due to supply chain chaos resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Industry experts widely agree that prices will return to their previous trajectory as the supply chain returns to a pre-pandemic normal. Lithium batteries are expected to reach under $100 per kWh by 2024.46 Given their mass production and versatile deployment, lithium-ion batteries will likely dominate our energy storage landscape for the foreseeable future.

Flow Batteries

Flow batteries are a type of battery that uses conductive liquid electrolytes which are pumped – or “flow” – from tanks through a flow cell. Two different electrolytes are kept separate within a flow cell by a membrane that divides the cell in two, but which permits charged particles to be exchanged between the electrolytes. The electrolytes generate electricity when they react with the conductive electrode on their side of the membrane.47 The nature of the technology means that, in order to achieve large storage capacity, the batteries must be large and heavy, limiting their use for many applications where smaller batteries are required, but also making them ideal for grid-scale utility storage, where size and weight are less relevant. A significant advantage of flow batteries is that a battery’s storage capacity can be increased by simply getting bigger tanks for the liquids, instead of having to buy additional stand-alone batteries.48

Flow batteries can provide power for up to 10-14 hours. The long duration capabilities of a flow battery give it an advantage over lithium-ion batteries when used for utility-scale storage.49 Flow batteries have an operating life of 25 years compared to an expected life of 8 years for a lithium-ion battery that was cycled daily. When used at a large scale, flow batteries are expected to be low-cost.50 Flow batteries also are safer as they are not at risk of fires, which can be a problem with lithium batteries.51

The flow battery industry is still in its infancy, and, as with most areas of the energy transition, supply chain issues are currently one of its main challenges.52 Another challenge is meeting the overwhelming demand for these batteries. ESS, a leading U.S. manufacturer of iron flow batteries has more demand for its products than it can currently fulfill. The company expects to have 25 MW of manufacturing capacity by the end of 2022, and to quadruple to 100 MW by the end of 2023.53 Several flow battery projects are underway in the U.S., including one for the U.S. Department of Defense that broke ground in November 2022, and another for the California Energy Commission.54

EVs

One of the most significant sources of battery storage is one that is still not widely integrated into the grid: the millions of EV batteries that will soon be on the road and plugged into charging stations for hours at a time. When EV batteries are plugged into charging stations, they can send power back to homes and the grid. This process is known as bidirectional charging. Bidirectional charging will allow utilities to use the power stored in EV batteries to provide low-cost energy to consumers and increase grid flexibility.55 An average EV battery can store around 66 kWh of usable electricity which could be called upon by utilities in times of need — enough to mitigate sudden demand surges or loss of generation capacity.56 Some EV batteries can even power a home for up to three days.57 Bidirectional charging is a relatively new technology, but it is being integrated into new EV models.

The benefits of using EVs as energy storage are immense. EV battery storage will make the transition easier for average Americans and private corporations by reducing the amount of investment needed to meet America’s climate goals. Most Americans already rely on their car for daily transportation, and all Americans will need to convert to EVs over the next couple decades. Using EVs as energy storage can help Americans satisfy both their transportation and home storage needs with a single purchase. EV owners can be compensated with credits on their utility bill for electricity sold back to the grid, and can earn up to $3,000 per year.58

Utilities and private clean energy investors benefit by having to build fewer stand-alone energy storage systems, freeing up capital to invest in transmission or generation capacity instead. Early studies comparing the impacts on the grid of using EV batteries as energy storage relative to using stand-alone battery storage have shown that the same grid benefits can be achieved at a fraction of the cost when using EVs.59 Using EVs to reduce the amount of stand-alone or utility-scale batteries will reduce the overall demand for lithium – an already scarce resource needed for consumer electronics and clean technologies. Any investment in EV manufacturing and deployment is, thus, an investment in decarbonizing both the transportation and electricity sectors.

There are already more than 900,000 EVs on the road in America, and our National Mission for EVs lays out a plan for 100% of all new cars sold in America to be electric by 2035, and for the entire fleet of passenger vehicles in America to be electric by mid-century.60 The high number of EVs that will be on the road by 2035, the vast majority of which will have bidirectional capabilities, will allow EVs to become a critical form of energy storage in the US.

Hydrogen

Electrolyzer and fuel cell technology allow curtailed electricity to be used to create hydrogen from water, which can then be stored and converted back to electricity when needed. Using hydrogen for LDES requires that storage sites be paired with on-site renewable generation. Where this isn’t possible, transmission lines will bring renewable energy to the storage site. A real advantage for green hydrogen production compared to methane-based hydrogen production is that green hydrogen can be produced anywhere there is water and a supply of clean electricity. It does not require the massive production and distribution system necessary for methane-based hydrogen.

While hydrogen can be stored above ground in metal tanks, the most economical solution for storing large amounts is one that is already employed by the oil and gas industry for storing crude oil, natural gas and hydrogen — storing it in underground salt caverns.61 Much of the current seasonal storage for natural gas is stored in underground formations, and so is the crude oil in the U.S. strategic petroleum reserves. Caverns now used for natural gas storage can be repurposed for hydrogen storage. Indeed, hydrogen has been stored in salt caverns in the Gulf Coast for decades.62 There are already three salt caverns in Texas being used to store hydrogen. They are not for energy storage per se; instead, they store hydrogen for industrial consumption. Although salt cavern storage is constrained by geology, the U.S. is fortunate enough to have several locations across the country where hydrogen can be stored.63

Private companies are already investing in the potential of hydrogen storage in salt cavern as an LDES solution. The Advanced Clean Energy Storage (ACES) project in Utah is an example of this, with plans to combine salt cavern availability at a former coal power plant site with existing grid connections that allow it to integrate easily with the western U.S. power grid, all focused on the goal of providing LDES for California. One aim of the project is to provide seasonal storage for the California power market, storing excess power generation from the spring, and supplying it back during periods of peak demand in the late summer.

The single salt cavern proposed as part of the ACES project will be able to store 150,000 megawatt hours (MWh) — an amount of energy 125 times greater than all of the installed battery storage in the U.S. at the end of 2020.64 The average U.S. household uses approximately 0.9 MWh per month. One storage cavern, then, could power approximately 160,000 households for a month. The operators of the Utah project claim that the salt formation has enough capacity for 100 of these caverns, the equivalent of energy storage to supply 16 million households for a month. There are approximately 15 million households in California. This is an eye-opening prospect.

Molten-Salt

Molten-salt batteries are a type of battery that can store power for weeks or months at a time. They use salt as an electrolyte, which changes from solid to liquid when heated. Melting the salt allows its constituent charged ions to flow through the battery. Applying an electrical voltage to the molten electrolyte causes its ions to separate out according to their electrical charge. This electrolyzing process requires energy which can be provided to the battery from clean sources. Once the battery is fully charged, the battery is placed in a room-temperature environment. The drop in temperature causes the molten salt electrolyte to solidify in its newly separated arrangement, thus storing the energy in the battery until it can be melted again.

Molten-salt batteries are still in their infancy and have yet to be widely commercialized, but, if successfully deployed, they would provide many benefits to the power grid and be an essential form of seasonal storage. Their primary advantage over other types of batteries is that they have remarkably lower discharge rates — the rate of energy loss while a battery is not in use. Early tests show that a molten-salt battery can maintain 92% of its charge over a three-month period, and around 80% over a 6-month period.65 Molten-salt batteries could be charged during the summer, when solar generation is at its peak, and then discharged during the winter, without utilities having to worry about whether the battery would already become depleted in the interim. Molten-salt batteries have a long lifetime, around 30 years, and can withstand frequent use.66

There are still barriers preventing the widespread use of molten-salt batteries. Most molten-salt batteries have a high heating point of around 180 degrees Celsius, and the energy used to thaw the battery is the equivalent of around 10-15% of the battery’s total capacity.67 Researchers appear optimistic that they can lower the working temperature, but it is unclear what the final result will be. The high working temperature will limit the battery to mostly industrial settings. Most advanced molten-salt batteries are still in the development stage and are around five to ten years away from commercialization, so the final cost of manufacturing the batteries is unknown, and it is unclear whether they will be financially competitive with other potential forms of seasonal storage.

The Urgent Need for More Electricity Transmission

Building more power transmission lines is one of the biggest obstacles to getting to a 100% clean power grid. We need more long-distance, high-voltage transmission lines in order to move power from areas where wind, solar, hydroelectric, and nuclear power are abundant to places where energy demand is high. But we will also need thousands of miles of new short-distance lines to connect new clean power facilities to the grid, and to connect new high-quantity consumers of power to the grid, such as hydrogen production facilities and charging clusters for electric truck fleets.

The problem is not that it’s difficult to build power lines — transmission lines are a simple technology that Americas has been building for more than 150 years — it is that the process of approving new power lines is pathetically slow. Most transmission line projects must pass through multiple layers of approval processes by many different agencies at local, state, regional, and federal levels. All of the agencies involved are understaffed and working with a set of processes and rules that could not be more inefficient if they were intentionally designed to be so. Some of these rules are imposed by counterproductive legislation. Others are just a matter of tradition and carelessness.

Additionally, projects only get off the ground and reach fruition when utilities and regional transmission organizations (RTOs) are able to accommodate them. Here, again, these organizations are often working with inadequate staff and with perverse incentives deriving from the upside-down business models of utilities in which they reap greater rewards the more slowly and inefficiently they invest.

Finally, in the course of approval processes for power lines, if anyone in the community affected by a project opposes it, this can greatly delay or kill the project altogether. Delays themselves can kill a project if investors get cold feet and pull out.

There is no reason why transmission lines should be any more difficult to site than other pieces of energy infrastructure. Those get built, however, because even though there are complex, multi-level review processes, and even though citizens are free to object and demand compensation, an ultimate decision-maker exists that can say yes to these projects. In the case of natural gas pipelines, for example, the FERC is that final decision-maker. It was given that power in the Natural Gas Act of 1938. The fracking boom that revolutionized U.S. energy over the past few decades was in part made possible by the FERC having this power to give the final and definitive go-ahead for new gas pipelines. Interstate transmission projects, on the other hand, have no codified final decision-maker.

Our proposals in this mission call for giving the FERC the same authority over electric power projects as it has over natural gas projects and giving the federal government more power to fund and build projects on their own. But it will take more than that, because organized anti-clean-power groups, and the companies that fund them, are going to keep fighting to stop any project that will lead to more clean power. That is why this mission requires the president to change our culture to make it more unacceptable to accept defeat when it comes to building things that our society needs. Change of any sort is always opposed. We used to have a culture that listened to, compromised with, and compensated opponents, and pushed ahead when change was necessary and beneficial. Today, we have a culture where regulators, officials, and investors throw up their hands too quickly. This needs to change, and the president is the only person who can attempt to initiate that change. We devote part of this mission to political strategies that will work toward that end.

Nuclear Power

Nuclear power is a highly controversial topic among environmentalists and energy policy wonks.68 Many fear that nuclear power is too dangerous to include in America’s energy mix. Even though nuclear accidents have been extremely rare, and even though the few that have happened took place in old plants in other countries, many argue that nuclear accidents are so catastrophic that the only acceptable risk of one happening is zero. Many opponents of nuclear power also argue that it is too expensive and difficult to build nuclear power plants today.

Supporters of nuclear power contend that it is the safest form of energy the world has ever known, if you count actual deaths and injuries caused by all kinds of energy generation.69 Even solar and wind kill more people per unit of energy produced in manufacturing and installation accidents, and in failures such as blade malfunction and wind turbine fires.70 The effects of pollution from burning fossil fuels, which nuclear could help us replace faster, kill millions of people every year.71 Moreover, many nuclear supporters argue that it would be the cheapest and easiest-to-maintain form of power available, if we changed regulations to make it easier to build nuclear plants and then rebuilt a robust nuclear industry.72

But passions run high on this topic. It can be difficult to discuss the facts of how dangerous nuclear power really is because radiation has taken on a kind of mythical identity as something uniquely and almost infinitely dangerous. Radiation is not released from normally-functioning nuclear plants. In fact, a coal plant releases much more radiation than a nuclear plant because of naturally occurring radiation in coal. By design, a nuclear plant is far less radioactive to its surroundings than the ordinary background radiation of buildings, the ground, or the sky. In rare nuclear accidents, however, radioactive gasses have been released intentionally, and in the case of Chernobyl and Fukushima, large quantities of radioactive gasses and liquids were released unintentionally. Many nuclear opponents believe that any amount of radiation being released in an accident would be so lethal that it’s unacceptable to allow any risk of that happening, no matter how small or unlikely.

Before addressing the issue of the risks and costs of nuclear power, we need to answer why we are talking about nuclear power at all. Nuclear power plants are capable of producing very large amounts of power and do not emit greenhouse gasses or any other kind of air pollution during the generation process. They don’t have intermittency issues, and can run consistently for decades. Once they are built, the cost per unit of energy of operating and maintaining them is extremely low even compared to comparative baseload fossil fuels. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for existing coal is about $41 per megawatt-hour (MWh), natural gas is about $36 per MWh, and nuclear is only $33 per MWh.73 Also, even compared to solar and wind power per unit of energy, nuclear power requires far fewer natural resources and has a far smaller greenhouse gas footprint.74 A wind farm that produces the equivalent amount of power to a nuclear power plant requires massive quantities of land, significant natural resources and labor to manufacture, and extensive amounts of energy to transport across the planet to their installation location. For some of the duration of the Mission for America, the work of building and transporting wind turbines and solar panels will be mostly powered by fossil fuels. Moreover, the transition away from fossil fuels will require so many natural resources that less resource-hungry technologies are very beneficial. For all these reasons, nuclear power is an attractive zero-emissions solution to powering the planet.

Our assumptions going into this project were that nuclear power was too risky and too expensive to be seriously considered. Upon closer review, however, a different picture emerged. We make the full case for nuclear power in a separate chapter covering the national mission for nuclear energy. Here we will just briefly answer the questions about risks and costs.

First, accidents that would release high levels of radiation are made incredibly unlikely by new nuclear reactor designs.75 However, it is unwise to say in any field that an accident is completely impossible. If nuclear critics are correct then a nuclear accident would be so catastrophic that any chance of an accident — even approaching zero percent — is unacceptable. Therefore, let’s talk about how dangerous a nuclear accident actually is.

The reality is that even the worst nuclear catastrophe in history, the Chernobyl disaster, harmed millions fewer people than a single year of burning fossil fuels. An estimated 7 million people die each year from air pollution from fossil fuel use, with brown coal, coal, and oil as the top three sources of pollutants.76 Furthermore, a 2013 study published by the American Chemical Society (ACS) shows that the displacement of fossil fuel use by nuclear power has prevented nearly 2 million air pollution-related deaths and has the potential to save millions more.77 In the Chernobyl disaster, 31 people were killed directly by the meltdown, and another 34 workers died later from exposure to extreme levels of radiation at the site.78 Radioactive gasses that escaped from the plant quickly dispersed in the atmosphere to undetectable levels.79 There are various estimates of how many people might have gotten cancer later from exposure to elevated levels of radiation in the surrounding areas. While it is impossible to know exactly how many that would be, credible estimates range from zero to 5,000.80

But even if the death toll was 5,000, what is important to keep in mind is that 5,000 deaths from one freak accident is millions fewer deaths than what is caused by the normal operation of our fossil fuel economy.

One other way to put the Chernobyl disaster into context is to consider that the United States has detonated more than 1,000 nuclear bombs in military tests. Combined with other nations, the world total for nuclear detonations is more than 2,000. Many of these were carried out within the continental U.S. right in the open air. In many cases, far more radiation was released into the atmosphere than from the Chernobyl disaster. Of course, we are not arguing that that was acceptable. It absolutely should not have happened. But it puts something into perspective: If radioactive gas being released from a reactor is a world-ending event, then how did we get through 2,000 nuclear bombs being detonated without catastrophic effects for the world?81

Besides safety, the other major argument against nuclear power is that it is more expensive than solar and wind. That comparison is, however, both unfair and inaccurate. Once a nuclear power plant has been built and is operational, its per-unit cost of power is far lower than that of any other form of power generation.82 The problem is that the construction costs of building new nuclear plants have spiraled out of control in the United States and in many — but not all — other countries.83

Two factors are driving the rise in construction costs: Poor regulation and lack of scale. The current state of nuclear power regulation in America is broken. Nearly all American nuclear power plants came online between 1970 and 1990, with a significant slowdown following the Three Mile Island accident in 1979.84 The most recent plant to enter service is Watts Bar 2, which came online in 2016: the first plant to do so since 1996.85 Overall, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which was created in 1975 and oversees the industry, takes an average of 80 months to approve new construction and operation licenses.86 This contrasts with the United

Kingdom which averages a 54-month approval process.87 The most recent approvals in the U.S. came in 2012 for two reactors at Vogtle in Georgia, and two more reactors at the Virgil C. Summer plant in South Carolina. Since then, Vogtle has seen significant delays and has cost a whopping $30 billion, while construction work on the new reactors at the S.C. plant was stopped.88 We will discuss this problem in depth in the chapter devoted to the national mission for nuclear power, but the crux of the problem is that the NRC was charged with pursuing a policy of zero risk tolerance in nuclear plant operation.89 In practice, this is impossible and has made it incredibly difficult to build new plants.If nuclear plants were regulated by the same agencies and according to the same principles as other energy facilities, they would be far cheaper to build and just as safe.

The other factor driving the rise in construction costs is lack of scale. We have gone so long without building nuclear plants that we have lost access to the specialized categories of workers and companies that are needed to build them.90 In China, where they are building many nuclear plants at any given time, a body of specialized workers and contracting companies has grown up around the industry and gets more experience with each new plant. In the U.S., workers and companies must approach many tasks involved in building a new nuclear plant facility with no experience, which is incredibly difficult and, thus, very expensive.

The Promise of Geothermal

Geothermal energy is a renewable energy source that uses heat stored beneath the Earth’s surface to generate carbon-free electricity. Geothermal plants drill wells deep below the Earth’s crust until they reach locations where hot water or steam reservoirs exist. The system directs the extracted hot water or steam to a geothermal power plant, where it drives turbines connected to generators, converting the thermal energy into electricity. Geothermal is a form of baseload energy generation that can run for 24 hours a day and helps fill gaps from intermittent sources.91

Geothermal energy provides only a small amount of total U.S. power and the geographical limitations of the technology makes further deployment difficult There are 61 geothermal power plants in the United States with a total capacity of around 3.7GW — or around 1% of total energy capacity.92 Conventional geothermal power is heavily constrained by geographical factors, as there are very few areas within the United States with existing fissures that contain enough underground water or steam to generate a relevant amount of power. Nevertheless, opportunities for modest expansion of conventional geothermal capacity exist. A recent DOE study estimated that around 60GW of new geothermal energy could be added to the grid by 2050.93 Even with an additional 60GWs, geothermal energy would still make up a small part of the total U.S. power grid.

Researchers have spent decades working on enhanced geothermal technologies that overcome the geographical constraints of geothermal energy. Enhanced geothermal technologies re-open existing fissures or create new fissures in the Earth’s crust and then pump water into them to create a reservoir.94 Enhanced geothermal projects can create reservoirs thousands of feet underground, enabling projects to reach deeper and hotter areas of the Earth. This advancement allows for projects in areas previously unsuited for geothermal use.

While the potential of enhanced geothermal is undeniable, its journey has not been straightforward. The first enhanced geothermal plant in the U.S. was built in 1973 in Fenton Hill, New Mexico.95 Yet, despite the tech having been around for half a century, it has struggled to scale beyond a few experimental wells. Project developers have struggled with drilling deep enough, finding hot enough reservoirs, and have had to manage risks around seismicity.96 Managing all of these concerns is expensive, and enhanced geothermal plants have struggled to be cost-competitive with other forms of energy generation.97

Recent developments may signal that enhanced geothermal has turned a corner and is ready for widespread commercialization. In mid-2023, the company Fervo Energy announced that they have a first-of-its-kind licensed, fully operating enhanced geothermal power plant. The Fervo project uses two separate horizontal wells and drills down to 3,250 feet before drilling sideways to produce more wells.98 The project reached a temperature of 191 C (375.8 F) and achieved a notably high flow rate. The project had a power output of around 4MW, a small but promising start.

The Fervo project still has issues to work out before it can be declared a true solution to the ills of the geothermal industry. Namely, it is still far too expensive compared to other forms of energy generation. As of writing, the exact MWh cost of the Fervo project is not publicly available. However, the Fervo CEO has stated that the cost is “significantly” higher than the DOE goal of $45/MWh for geothermal generation.99 It is reasonable to assume the cost will decline as Fervo builds more projects and the company learns how to reduce costs. However, there is no guarantee that the price will ever decrease enough for widespread deployment.

Fervo is not the only company investing heavily in promising enhanced geothermal technology. AltaRock is using a different type of enhanced geothermal called SuperHot Rock geothermal. Quaise Energy is focusing on drilling incredibly far down to get to hotter temperatures. Similarly to Fervo, these companies all have promising but unproven new technologies. All of these projects may fail, or any one of them may revolutionize the geothermal industry.

It is simply too early to tell what the future of the geothermal industry will look like. Due to this uncertainty, we do not intend to make geothermal the foundation of our clean energy plan. At the same time, we want to recognize the industry’s potential. The geothermal industry is an excellent opportunity for public and private investment. The government should dedicate substantial resources to new research and development and back promising startups that arise in this sector. The growth of an enhanced geothermal industry could power millions of American homes, create jobs for workers displaced from the fossil fuel industry, and facilitate the transition to a 100% clean energy grid.

The Comprehensiveness of the Mission for America and the Clean Power Mission

The various parts of the national mission for clean power mutually support each other — just as they do within the other missions. At the same time, all the various national missions mutually support each other within the larger Mission for America project. As discussed in the introduction, doing more in a comprehensive way is very often easier than doing less in the form of individual projects in a one-off manner.

Within the Clean Power Mission, comprehensiveness is key in several areas. Financing will flow adequately thanks to government financing, guarantees, purchase agreements, and other forms of investment offered by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Clean energy projects will be enabled by comprehensive upgrades to utility infrastructure, technology, and transmission. A clean energy standard and generous clean energy subsidies are the drivers that bring it all together. Any one of these carried out in isolation without the others would have a positive impact but would fail to transition the grid to 100% clean power. Only when executed together will these policies accomplish the goals of this national mission.

One example of how our proposals in this mission will be easier to achieve together than alone is the Clean Energy Standard (CES). A CES requires utilities to replace fossil fuel generation with clean energy sources over a set period of time. The CES is already a mainstream proposal that has support among many Democrats in Congress. The CES is one of the most powerful tools the federal government has and is the cornerstone of this mission. However, it will be incredibly difficult for utilities to comply with any clean energy standard, on any reasonable timeline, without the other proposals in this mission. Utilities will need to spend billions of dollars upgrading their systems to be ready to handle 100% clean energy. Most utilities in the United States do not have the money or technical expertise to successfully make those upgrades on their own. Therefore, the federal government will need to step in to provide financing and technical assistance — far beyond what is offered currently — to utilities throughout the duration of the energy transition.

The comprehensiveness of this mission not only will make the mission easier to complete, but will also make it easier to enact in Congress. Without the money and support offered by this plan, utilities would fight against the CES tooth and nail, knowing that it would be difficult or impossible to comply with. Of course, they will still fight a CES, even with all the perks we are proposing for them. But these perks will allow the president to win many utilities over, to soften the opposition of the rest, and to explain to both Congress and the public that opposition from utilities is rooted in a knee-jerk opposition to change of any kind. This is the same type of opposition that has knee-capped American growth and prosperity — and the same type of opposition the Mission for America will overcome.

Solutions

The solutions presented below aim to transition the U.S. power grid to 100% clean power by 2035. The overall approach combines economic incentives with regulatory mandates, buoyed by executive leadership and a vision for a resilient, clean grid. Our solutions here rely heavily on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) which will offer crucial coordination, investment capital, and other types of support to industry players of all sizes. Congress must pass sweeping legislation, including: a Clean Energy Standard mandating utilities invest in clean energy generation, new tax credits for clean energy manufacturing and deployment, and sweeping reforms for permitting and siting new transmission lines and clean energy projects. As with all other national missions, the clean power national mission will require bold and direct leadership from the president, their administration, and the RFC’s clean power team.

Solution 1: Creating a Clean Energy Standard (CES)

The Challenge

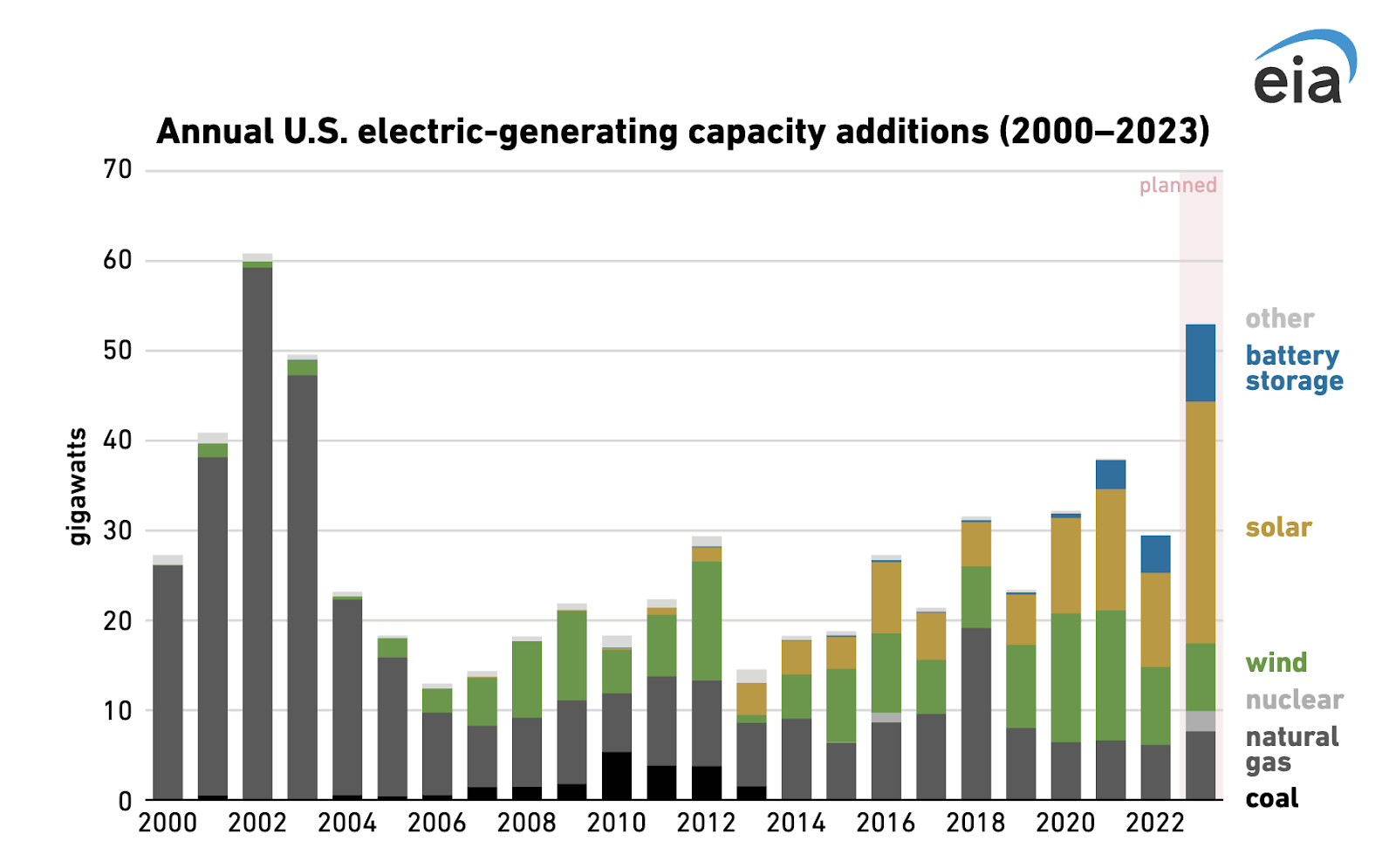

The share of power generated from clean energy in the United States, such as wind and solar, is rising every year. The United States generates over three times more wind and solar power than it did 10 years ago.100 The vast majority of new capacity added to the grid since 2019 is from clean energy sources — and the lead is growing every year.101 In the first quarter of 2023, close to two-thirds of new utility scale generation capacity was from clean energy sources.102 It is fair to say that the current rate of clean energy deployment is far beyond what many expected was possible 10, or even five, years ago.

Unfortunately, as inspiring as the pace of deployment may be, it is still insufficient.103 Given the current model for building out clean power, each additional step toward 100% clean energy will be more difficult than the last. For example, suitable sites for new clean power facilities get harder to find as they are used up.104 Existing clean energy policies may get us to 50% or even 80% clean power relatively quickly. That next 20%, and especially the last 10% or 5%, will be much more difficult. At the current rate of deployment, it will take another century to convert the electric grid to 100% clean energy.105 That timeline would guarantee the world surpasses 2 degrees of warming. Avoiding that catastrophic outcome will require a fundamentally different approach than the one we are currently using.

A Clean Energy Standard (CES) is the foundation of any viable plan to get the nation to 100% clean power. A CES refers to a federal policy that sets clean energy generation benchmarks for utilities across the country. Instead of merely encouraging investment in clean power, it requires that utilities phase out fossil fuels and get to 100% clean power by a specific date. Our CES calls for 100% clean energy by 2035, with a strict definition of clean energy that excludes all fossil fuels. In this mission for 100% clean power, the CES provides long-term guaranteed demand for clean energy, unlocking billions in private financing that is still standing on the sidelines. The national commitment provided by the CES will tip the playing field in favor of clean power investors and developers, making it easier for them to overcome the many obstacles to building the capacity we need to meet the goal of 100% clean power.