At a Glance: The Mission for America

The Mission for America is a comprehensive, 10-year plan to overcome the twin crises facing the United States and the world:

The failure to provide expected economic security and progress for most Americans and billions of people globally — a failure that is breaking the international post-war social compact and threatening the survival of liberal democracy; and

the failure to avert catastrophic global warming, which, if the trend of the last few years continues, threatens life on earth as we know it this century.

This first edition of the Mission for America lays out a detailed plan for what could be achieved in ten years given expected economic, environmental, and technologic realities of the near future. We have designed the Mission for America to be feasible given only one change in the political landscape: That a U.S. president with a bold and unified team wins a simple majority in both chambers of Congress (and suspend the filibuster) — and that they do so by enlisting the country in this Mission for America, or something like it, to reverse national decline, avert deadly global warming, and build a sustainable economy capable of providing prosperity for all.

In this general introduction, we cover the central concepts, institutions and tools of the Mission for America, starting with the idea of a national mission itself. The Mission for America is divided into a number of projects which we call "national missions," each of which transforms a different sector of the economy or solves a significant problem. Reading a single national mission on its own, one might judge that it's too ambitious to be possible in a 10-year timeframe. The key to understanding the Mission for America is to see how the national missions work together to make each other possible.

Most U.S. climate plans aim only to reduce domestic output of greenhouse gasses. The Mission for America, on the other hand, is primarily designed to achieve an international climate goal as well as a domestic one. The U.S. accounts for only 15% of global emissions. Bringing the U.S. economy all the way to zero would barely affect the world's trajectory toward catastrophic warming. That's why the Mission for America is designed around the goal of supplying the world with everything it will need to get to net-zero as rapidly as possible, including technology, machines, materials, services, financing and leadership.

The Mission for America is based on an intellectual and policy framework of abundance. A national economy as large and advanced as America's is not a zero sum system. Reindustrialization does not come at the expense of our other national priorities — it's how we fulfill them.

Every modern industrialized nation except the U.S. has coordinating and financing institutions capable of activating labor capital on a large scale to develop new capacities and real wealth. The Mission for America calls for restoring our nation's capacity for public investment and economic coordination — primarily in the form of the World War II-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation — to drive not only economic growth and rising wealth, but the development of a sustainable economy that can provide prosperity for all.

About the Mission for America

The Mission for America is a comprehensive plan to overcome the twin crises facing the United States and the world:

The failure to provide economic progress for most Americans and billions of people globally — a failure that is breaking the international post-war social compact and threatening the survival of liberal democracy; and

the failure to avert catastrophic global warming, which, if the trend of the last few years continues, threatens life on earth as we know it within the century.

This is the first edition of the Mission for America. It has been written as a thought experiment for what would be possible to accomplish in 10 years given a president willing and able to call the nation to a full-scale mobilization to address both sides of the double crisis we face.

The Mission for America is organized into a number of component national missions that achieve specific goals. When you’re reading about one of them, you might judge that it’s too ambitious to be possible in a 10-year time frame. The key to understanding the Mission for America is that all national missions work together as a comprehensive whole to make each other possible. In each mission’s chapter, we show how other missions make seemingly impossible or difficult feats possible — or even easy — for that particular mission. In this general introduction, we cover the central concepts, institutions and tools of the Mission for America, starting with the idea of a national mission itself.

America has everything it needs to solve its economic crisis. The primary mechanism for doing that is to solve the global climate crisis. The two crises can only be solved together. Playing our part to transform the global economy to stop global warming is the only challenge big enough to provide high-wage employment for all Americans; at the same time, fully mobilizing our economy is essential to building a global clean economy in the time we have left before global warming spirals out of control. For the United States, building a global clean economy is a miraculous business opportunity that can restore broadly shared prosperity. It is also a solemn practical and moral responsibility.

The Mission for America is designed to achieve an international climate goal. Most U.S. climate plans aim only to reduce domestic output of greenhouse gasses. But the U.S. accounts for only 15% of global emissions. Bringing the U.S. economy all the way to net-zero would barely affect the world’s trajectory toward catastrophic warming. That’s why the Mission for America is designed around the goal of supplying the world with the technology, equipment, machines, materials, goods, and services it will need to get to net-zero as rapidly as is physically possible. Additionally, the U.S. will need to provide skillful international leadership and financing on highly favorable terms for low- and middle-income nations. Bringing U.S. emissions as close to net-zero as possible, as fast as possible, is also part of the Mission for America, because this will set an example for other countries, raise expectations for what nations can accomplish in a short time, and provide a guaranteed domestic market to prime the pump for the industries we must build to supply the world.

The U.S. has a practical responsibility to help supply and lead the global transition because we hold so much of the world’s capacity for accomplishing it. The present state of the climate crisis is like a building that is burning while four fire trucks are parked at a gas station next door with the crews standing in line for coffee. The U.S. is one of those trucks, the others being China, Europe and the rest of the world — each representing roughly one quarter of the planet’s GDP and manufacturing capacity.1 In the race to overhaul global industry and infrastructure, the U.S. is an absolutely essential inventor and producer. Many of the world’s fundamental green technologies were invented in the United States, though we have neglected to build the mass manufacturing capacity here to supply global markets. The U.S. contains only about five percent of the world’s population, but it produces one quarter of global GDP and contains 17% of its manufacturing capacity, including some of the most technologically advanced and high-value manufacturing capacity in the world.2 Even after all the economic and political blunders of the past several decades, the U.S. remains the indisputable world leader with regard to both financial and military power.3 If any major part of the world fails to rise to the industrial challenge of building a new, clean economy, then we will encounter catastrophic global warming. The U.S. is one of those major parts, and for the reasons just mentioned, perhaps the most important. We have a responsibility to add to the total industrial capacity of the world available for the green transition both because it is needed and because we have the means to supply it.

That is our practical responsibility, but we are also bound by a moral responsibility: The U.S. is the source of 25% of the cumulative greenhouse gasses that are heating the planet — far ahead of any other nation.4 Our nation accumulated its incredible wealth and power over the past century, fully aware for much of that period that we were changing the composition of the atmosphere in a way that would heat the planet. The warming effect of carbon dioxide was known as early as the late 19th century.5 We pumped trillions of tons of it into the atmosphere anyway. Now we have a responsibility to use that power and wealth to undo the damage and to work with the rest of the world to accomplish a transition to a clean economy.

If U.S. political leaders had to campaign for the Mission for America purely on the basis of our moral responsibility, there would be no hope. Fulfilling our responsibility, however, just so happens to be the only path to providing shared economic prosperity and progress for all Americans. Building a global clean economy is simply the only opportunity big enough to fully turn around America’s economic prospects.

For decades, a powerful fatalism has dominated American politics when it comes to economics and industry. First, experts on both sides of the aisle said we needed to retreat from manufacturing in the U.S. because we couldn’t compete with low-wage workers in developing countries. Rather than invest in modernization and automation to compete, we simply gave up on entire sectors of our industrial economy.6 As a result, millions of Americans lost high-wage industrial jobs and entire regions were economically devastated, setting the stage for the rise of anti-democratic, right-wing political movements.7 Then, when China and other rapidly industrializing nations moved into capital-intensive industries where wages are a very small factor, the same experts said we had fallen too far behind in manufacturing to ever catch up again, and good jobs continued to flow out of the country.8 Under both presidents Trump and Biden, that fatalism has started to be replaced by attempts at reconstructing a U.S. industrial policy. But the programs initiated so far are only drops in the bucket compared with what is necessary and what we are calling for in the Mission for America.9

The most remarkable thing about America’s strong global political and industrial position is that it survives after decades of underinvestment and social and economic decline.10 Decades of laissez-faire policies initiated by both parties gutted the public sector, shut down national industrial policy, offshored jobs, and encouraged financialization across the economy. Corporate profits continued to soar, but millions of American workers suffered the consequences of these actions.11 Nevertheless, the U.S. economy continued to grow in terms of total GDP — thanks in part to its centrality in global financial and consumer markets and the U.S. dollar’s status as the global reserve currency. However, gains were unequally distributed to the extreme.12 Disastrous and unpopular wars in the Middle East badly damaged America’s global credibility — yet it remains, at least for now, a global hegemon. America’s leadership has persisted through these failures because, despite everything, the foundations of its economy, international standing, and democracy are exceptionally deep. The Mission for America is a dream for what America could achieve if it utilized, rather than undermined, its wealth and global position.

The Mission for America is based on an intellectual and policy framework of abundance. A national economy as large and advanced as the U.S. economy is not a zero-sum system. Reindustrialization does not come at the expense of our other national priorities — it’s how we fulfill them. Modern industrialized nations have coordinating and financing institutions that activate labor and capital to build up capacities and wealth. Without those institutions, an economy is like an organism that no longer grows. The U.S. used to be well equipped with those growth institutions, but they were dismantled after World War II as part of the general transition to neoliberal management of the economy and due to other peculiar American political factors. The Mission for America calls for restoring our nation’s capacity for public investment and economic coordination.

America will be able to confront its twin crises only once its leaders across the public and private sectors can dream it is possible to do so successfully. New Consensus is a non-partisan think tank. We hope this plan influences whatever administration occupies the White House, Congressional leaders and their staff, journalists covering economic policy, and other policy leaders in 2025 and beyond. We intend to update and expand the Mission for America for the 2028 cycle and every subsequent presidential cycle to account for political, economic, climate, and technological changes. Our aim is not that future leaders adopt or endorse it by name, as many did in the 2020 campaign cycle with the Green New Deal, but rather that they will adopt the underlying ideas and make them their own. For that to happen, they need to see a detailed, realistic plan that spells out exactly how it is possible to accomplish the enormous goals of providing prosperity for all Americans while supplying the world with everything it needs to stop global warming before it is too late. That is the purpose of the Mission for America.

Leaders can either pitch a national mission to their people in elections or propose it while in office, for example, in response to an emergency or as a proactive plan for breaking out of decline mode. We understand that in the U.S., without competitive primaries in either major party, no candidate will propose something like the Mission for America in 2024.13 We must point out, however, that it would be possible if someone chose to do it. The options for the Mission for America being launched in 2025 include President Biden in his presidential campaign declaring an emergency around climate change and cost of living and proposing something like the Mission for America as the solution to both. He could also do this after winning the election and make it his second term priority. As we write this, Donald Trump has made many speeches in which he promises to launch something that sounds like a national mission in 2025 if he is given the chance. Trump’s mission as stated includes massive investments in infrastructure and industry, the creation of entire new cities, as well as many other impractical and even bizarre proposals.14 As we write, the group called “No Labels” promises to run an independent candidate for president.15 It is unclear whether this will actually happen, and it appears that the platform of such a candidate will be merely to reestablish some version of a pre-Trump status quo.16 But nothing is stopping an independent presidential campaign from proposing something like the Mission for America.

We hope that this edition of the Mission for America will impact leaders holding office from 2025 to 2028 and help them to find more effective and comprehensive solutions to our biggest problems. More importantly, though, we hope it will expand the imaginations of those who will eventually go on to run for president and other offices in 2028, and all of those who will serve them. As we’ve said, after completing this edition, we hope to release an updated Mission for America in time for the 2027-28 Republican and Democratic primaries when candidates will be fiercely competing over ideas to solve both the climate and economic crises. Perhaps in 2028, serious independent candidates will also be running and looking for new ideas.

To pitch a nation on a mission, a leader must be able to first imagine it. Moreover, a leader cannot take a nation on a mission alone but must have the support of a network of other leaders, experts, staff, and participants in other roles who can imagine the mission and know how to operationalize it. Our purpose in creating the Mission for America is to enable and empower a new generation of leaders to imagine what is possible and to give them a detailed blueprint for making it happen.

America and the world after the Mission

The Mission for America is a mobilization of people, resources, and capital to accomplish tangible goals. If carried out successfully, America and the world will be different in many important ways. Before we dive into the conceptual underpinnings and policy intricacies of the Mission for America, we’ll highlight some of those concrete goals.

The following is just a partial list of what the Mission for America is designed to accomplish in 10 years if executed successfully:

Tens of millions of new, high-wage jobs will have been created.

Wages will have risen dramatically and conditions improved in tens of millions of already-existing jobs thanks to labor market competition with the newly created jobs.

Entire new industries will have been built, producing valuable and essential goods and services that either were offshored or were never developed in the U.S. — including industries necessary for the conversion to a clean economy.

Carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. will have been brought to near zero. Emissions of other human-caused greenhouse gasses such as methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gasses will have been dramatically reduced.

Nearly 100% of the energy produced on the nation’s power grids will be clean, including solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and nuclear. New long-distance, high-voltage power lines will ensure reliable and cheap power to every community in America.

A new institutional landscape will have been created that provides long-term financing and coordination for launching, scaling, and modernizing companies and industries in areas where private capital fears to tread.

Most homes and buildings will have been upgraded to achieve total decarbonization, improved energy efficiency, comfort, health, and safety — which will have created millions of high-wage jobs in the process. At the end of the Mission for America, most homes and buildings will produce no greenhouse gas emissions and will produce more energy than they consume.

Twenty to thirty million people will have been added to the full-time workforce through training and support services to discouraged workers and others not currently working full time, and by recruiting qualified foreign workers. (This goal could change depending on whether unemployment remains very low or rises with an economic slowdown or the mass displacement of workers by Artificial Intelligence or other forces. If unemployment becomes a problem, then this goal may have to be reframed to reemploy displaced workers in the U.S. instead of adding totally new workers to the workforce.)

At least 99.9% of cars on the road will be electric, thanks in part to building a dense fast-charging network that makes owning an EV more convenient than owning a gas-powered vehicle.

Batteries will have been developed and will be in mass production capable of powering large, long-haul trucks, and a charging and battery-swapping system to make electric-powered long-haul trucking feasible will have been built.

All rail transport will have been electrified. (This goal could change if another type of clean technology emerges to power trains.)

Technology for building and retrofitting long-haul cargo ships to run on 100% hydrogen will have been developed, and a hydrogen shipbuilding industry will be in full swing. We will have made significant progress toward transitioning shipping to hydrogen at least for ships going to, from, and around the U.S. Other technologies to make shipping more efficient, such as kites and sails, will have been developed and implemented. (This goal could change if another type of clean technology emerges to power ships.)

Hydrogen-powered long-haul aircraft will have been developed to replace large fossil-fuel passenger and cargo jets. Hydrogen-powered jet production will be in full swing. We will have gotten as far as possible toward converting the U.S. jet fleet to hydrogen. (This goal is also subject to change if another technology develops that turns out to be better than hydrogen for large jets.)

The U.S. will be the leading exporter of technology and equipment the world needs to reduce its emissions as much as possible, as fast as possible.

New institutions will have been established to provide financing and technical assistance to nations that need it to build clean economies. In 10 years, the U.S. will have made major deals around the world with low-interest financing over long periods, with provisions for loan forgiveness if clean economy plans are carried out.

Many new nuclear power facilities will be coming online on military bases across the country, providing reliable clean power to the whole nation — and importantly providing huge quantities of excess power to CO2 drawdown efforts and hydrogen production.

Billions will have been invested into discovering and developing new technologies to draw down or eliminate CO2 and other greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere, and viable technologies will be in service on a scale large enough to cool the planet.

The U.S. will have researched and tested last-resort methods for immediately and safely cooling the earth and will have solutions ready to launch at scale pending approval by the international community. Some example methods include releasing reflective substances into the upper atmosphere and installing mirror-cover in extremely hot population centers to reduce local temperatures.

In general, these and all the other Mission for America goals are designed to be achieved on a 10-year timeline. We address questions about the feasibility of that timeline in a section dedicated to that topic below. For now, it’s worth briefly mentioning some semantic issues around the 10-year time frame of the Mission for America. Sometimes, as a shorthand, we say that the U.S. will be at net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in 10 years. But there are too many unknowns when it comes to certain aspects of curtailing greenhouse gas emissions, such as those produced by agriculture, and unknowns regarding the feasibility of removing greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere, to be able to predict exactly how close to net zero is possible to achieve. The Mission for America is designed to get as far toward net-zero emissions as is physically possible — which, to be specific, we believe is at least 95% of the way.

A few of the emissions-reductions solutions are designed to be readied over the 10-year time frame, and then begin scaling up at or before the 10-year mark. These include hydrogen-powered aviation and shipping, and electrified long-haul trucking, which are a few of the very small number of technical problems that still must be solved.

As we envision these transformative changes in 10 years, it’s crucial to understand the historical context that necessitates such a comprehensive approach. The ambitious scope of the Mission for America not only aims to address immediate challenges but also seeks to rectify long-standing issues that have hindered our nation’s progress. This brings us to a reflection on our recent past, examining how America has deviated from its path of innovation and leadership.

How America stumbled, how we get back up

We used to build industries, infrastructure, and institutions to make life richer and more secure for each new generation. We did this as individuals, families, communities, businesses, and as a nation. We did it by competing and cooperating, by planning and executing. We embarked on great national missions that connected our communities by canal, rail, highway, and air; supplied the world with life-changing machines and materials; defeated fascism; and put people on the moon. By building in that way for three centuries, we achieved a level of freedom, security, and prosperity that our ancestors never dared to imagine. The world was watching. Patriotic leaders of every independent nation strove to emulate our success. Humanity came to expect that life for every generation should be easier, safer, and more abundant than for the last.

Then our leaders became possessed by a new idea: Society did not exist.17 The grand plans of the past did not drive progress. Planning and cooperating as a nation were, in fact, harmful. They shut down national economic development institutions.18 They stopped trying to repair and replace fading industries and let millions of high-paying jobs slip away. They starved public services and infrastructure of resources. Wages sank when compared with the price of essentials such as housing, transportation, healthcare, and education.19 America no longer made its own living, and wealth streamed out of the country as workers spent down their savings, governments and companies sold off their assets, and everyone borrowed. All this was based on a faith that if nations would only “get out of the way,” business would take off to new heights of innovation and investment.20

We learned through that experiment, however, that without coaxing and assistance from society at large, business will generally seek the easiest path to profits, which tends to be financial speculation, not economic development — even if over the long term that leads to lower growth for business as a whole.21 Though it did not happen immediately, most of the world followed the United States down the path of laissez-faire economics. Today, global business is stuck, generally afraid to invest on the scale that would quickly raise living standards for billions of people still living in poverty or reduce greenhouse-gas emissions fast enough to avert disaster from global warming.

The Mission for America is a playbook to get the U.S. economy unstuck. It is a plan for a total economic mobilization, modeled largely on the U.S. economic mobilization for World War II. Like the Mission for America’s aim to overcome global warming and the nation’s financial collapse, that mobilization was carried out to overcome two crises of its own: the Nazi conquest of Europe, and the crisis of confidence of business which culminated in the global Great Depression and created the conditions for the rise of fascism. The World War II mobilization was consciously designed to rely on, and remain within the bounds of, American political and economic traditions — which is how it won the support of business, labor, and voters of all political persuasions.22 The flexibility and dynamism of its approach allowed the U.S. to mobilize industry much faster and on a greater scale than European and Soviet command-and-control efforts. The state led the industrial transformation and mobilization, but the leaders were drawn largely from industry, and participation was voluntary and organized using the market mechanisms that everyone was already used to. As a result, the mobilization played out with far greater speed, scale, efficiency, and creativity than any economic development effort in history.23

As it was in the run-up to World War II, the American public today is divided. In the 1930s, most Americans did not support entering the European war against Hitler, even after he attacked America’s closest allies and began transporting masses of people to concentration camps. A large portion of Americans even supported Hitler and openly advocated for fascism as the only path out of the Great Depression.24 Only the attack on Pearl Harbor allowed President Roosevelt to take the U.S. to war. Today, a large minority of Americans believes that global warming is a hoax, and at least half do not see global warming as an urgent threat.25

This can change with the right political leadership. One condition for making the Mission for America possible is that such leadership comes along before it’s too late. We also believe that at some point in the near future, the world will have a “Pearl Harbor” climate event that causes an abrupt change to public opinion even in the U.S. If the accelerated warming trends of the past few years continue, dramatic changes will capture public attention: off-the-charts storms, new high-temperature records, and more unprecedented floods, wildfires, and droughts, including in places where populations are experiencing these for the first time. Even if these changes mostly devastate areas outside of the U.S., watching them on social media and television may be enough to shock Americans into a new frame of mind. This change in public perception of the climate crisis in the U.S. is another condition for the Mission for America to become fully plausible.

No matter how bad the climate crisis becomes, however, it is likely that most people in the U.S. will be able to live normal lives at least over the next couple of decades, the time frame in which urgent action must be taken. That is why the Mission for America must also include immediate and obvious economic benefits for all Americans, including those who will never care about global warming. Those who reject that climate change is happening can still understand that, for a variety of reasons, the world is moving away from the fossil fuel technology upon which the U.S. economy is based, which undeniably threatens American prosperity but also creates an opportunity. The Mission for America is designed to be equally a climate plan and a plan for reinventing our national economy to survive and thrive in the changing world of the 21st century — one that can power a political movement that draws at least some support from the half of America that is unconcerned with climate change. Because of the evenly divided nature of American politics, winning just a small amount of bipartisan support is the difference between victory and defeat.

The three modes of national action: a framework for thinking of national development

To manage their economic development, modern industrialized nations have three different modes of action: mission, maintenance, and decline. These describe a nation’s priorities, political and business culture, and available ways of acting in a given time. The Mission for America is a plan to return the U.S. to mission mode.

In mission mode, national leaders mobilize government, business, and other institutions to achieve goals. Beyond patchwork improvements to existing economies, this approach creates new industries, builds institutions, launches transformative infrastructure, and improves state capacity. Effective mobilization of people and resources in mission mode stems from a united focus on shared national objectives, lending legitimacy to the government and motivating voluntary participation from non-governmental institutions like labor unions and private industry. Goals that galvanize a nation are either typically urgently necessary or clearly beneficial to the populace. The Mission for America is designed to be both.

Mission mode is made possible by modern communication, transportation, and industrial systems that allow national and local governments, communities, businesses, and other institutions to coordinate effectively to accomplish big things. The history of the modern nation-state is the story of the emergence of this capacity. Leaders of pre-modern societies often worked to achieve big changes, but it was impossible to make big things happen in a short period of time without the communications technologies that power modern societies or the mass-manufacturing technologies that enable rapid changes to the physical capacities of a society today.26

In mission mode, challenges that seem impossible or difficult in other modes become possible, even easy. That’s why mission mode is not exhausting but is exhilarating, renewing, and makes a nation stronger every year that it strives to achieve its mission. Understanding this dynamic is key to understanding why the Mission for America is feasible, especially from within a society in decline mode, where such ambitious goals might appear unattainable.

Think of mission mode as the equivalent of running, maintenance mode as walking, and decline mode as watching TV on the couch. When you run, you’re using a different mechanism of movement from walking. You are flying through the air, occasionally tapping the ground with your feet. When you are walking, you are putting one foot in front of the other, with little speed or momentum. With walking, it is impossible to go very fast. Running allows you to go much faster — five to ten times faster. Moreover, running is efficient, requiring only two or three times the energy as walking. Significant speed is impossible or very difficult when walking, but it is easy when running, a far more efficient mode of motion. For a sedentary person who’s been physically declining for many years, however, running might feel impossible.

An example of mode-switching that made difficult tasks easier is the transition from craft production to mass production during the World War II mobilization. Initially, aircraft were made individually, by specialized craftsmen who built each plane as a slightly unique work, custom fitting parts that would not be interchangeable in other planes. This was necessary because mass manufacturing techniques had not yet achieved the precision required by airplanes, especially their engines. However, planners knew that the war’s demands necessitated mass production. This shift involved the aircraft industry being generously paid to teach the auto industry to build planes, and the auto industry adapting to higher-precision mass production than it had ever attempted before. Initially challenging, this transition drastically reduced the time and labor needed per aircraft. This switch from craft to mass production, detailed in the chapter on national mobilizations, enabled the U.S. to produce tens of thousands of large, new, modern airplanes in just a handful of years.27

Source: Hollem, H. (1942). Production. B-24E (Liberator) bombers at Willow Run. One of the assembly lines at Ford’s big Willow Run plant. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsa.8b05936/

In the World War II mobilization, the airplane mass production case was just one of thousands repeated across the economy. Virtually every industry was pulled “off the couch” to begin investing again in new capacities, new techniques, and new technologies. World War II investment and coordination institutions created dozens of entire new industries, such as the synthetic rubber industry which went from non-existent to producing nearly a million tons of rubber a year by the end of the war.28 Other industries that were jump-started, massively scaled up, or both, by World War II public institutions include aluminum, chemicals and petrochemicals, plastics, electronics, telecommunications, tanks, shipbuilding, aerospace and rockets, food processing and packaging, machine tools and industrial machinery, construction and infrastructure, and many others.29

But mission mode can’t be launched in single industries or sectors of the economy in piecemeal fashion. It demands a certain economy of scale. Part of this is the need for large institutions, such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), to finance and coordinate large-scale action, and that simply can’t work on the scale of a single industry. Shifting an entire industry into mission mode requires a collective openness to innovation and risk-taking, from leadership to line workers. As a general rule, that can be accomplished only by mobilizing the nation as a whole. While small groups, like startups motivated by making huge profits of world-changing products, can adopt similar behaviors, such widespread transformation in large corporations occur typically only in the context of a national mobilization.30

Many people misunderstand mission mode, assuming it can happen only in wartime. But most examples of national missions happened voluntarily in peacetime. All the European and Asian “economic miracles” from the 1960s to the 1990s were peacetime economic mobilizations.31 The U.S. mobilization around World War II, on which we have closely based the Mission for America, resembled a peacetime mobilization in many ways because the president began the mobilization when Congress and the majority of Americans were still adamant that the U.S. not enter the war. When Roosevelt began the mobilization, the U.S. perhaps felt less urgency about the crisis of fascism in Europe than it feels today about the crisis of climate change. Peacetime institutions under ordinary circumstances were sufficient to allow FDR to lay the groundwork for mission mode, even if it took the attack on Pearl Harbor for him to get the nation all the way there.

Like any powerful force, state power can be either harmful or healthy, destructive or creative. Early attempts by societies to mobilize economically with national missions did not always go well. Pre-industrial societies that were still one bad harvest from mass death were extremely vulnerable. Bad harvests could be caused by weather or blight and could be exacerbated by experimental or poorly designed policies of newly powerful states. Agriculture in early, industrial, capitalist societies tended toward consolidation around a small number of increasingly homogenous crops. This helped cause disasters like the Great Famine in British-controlled Ireland, during which food continued to be exported while more than one million people died.32 Agricultural and economic policies imposed by British rule in India were responsible for 50-100 million excess deaths, according to some studies.33 When the first totalitarian communist countries rapidly industrialized, they caused similar calamities, but on an even more concentrated and enormous scale thanks to their larger populations, the accelerated pace of change and greater control that modern societies could exert on populations, the lack of political institutions to protect people from misguided or malicious policies, and arbitrary and chaotic rule by dictators.34 Nevertheless, nations across various political systems learned from these experiences. Recent national economic development missions have generally seen rapid, steady progress, with inevitable missteps leading to easily resolved economic imbalances, not death. National missions are now safer and more effective.

Just because nations have the capacity to carry out missions to improve their economies doesn’t mean they always use it. Often, from mission mode, nations settle down into maintenance mode, seeking only to maintain current infrastructure, industry, and institutions. Nations in maintenance mode don’t necessarily begin disinvesting from industry or state infrastructure, but they don’t push for any significant expansions and offer only patchwork fixes to problems that arise.

Several different dynamics lead to nations leaving mission mode for maintenance mode. Powerful constituencies who felt their power was diminished under mission mode might reassert themselves by nudging society back to maintenance mode. This was the case after World War II in the U.S. when the representatives in Congress of Southern elites demanded the dismantling of national investment and coordination institutions. These institutions, having challenged white supremacy by providing employment opportunities in northern industries to southern Black workers, were seen as a threat to the existing power structure.35 Alternately, constituencies that were newly empowered by economic growth during mission mode might push for a return to the normalcy of maintenance mode in order to enjoy their newfound wealth without all the chaos and uncertainty of continued rapid growth.36 Another dynamic is that leaders can simply become tired after years of urgent growth and want to rest. If mission mode solved the crisis it was meant to, why continue?

Due to a mix of all three dynamics above, the United States began to slide into maintenance mode after World War II ended.37 Smaller missions were launched after World War II in partial attempts to keep mission mode going, including the space program and the War on Poverty. But the overall trend was to remove the state from the economy and let things continue however the “free market” determined.

Though corporations and small businesses had profited enormously through the World War II mobilization, as a constituency American business wanted to be free of the unrelenting demands of mission mode and take profits at a more leisurely pace using the capital that had been accumulated through the war. Right-wing business leaders, politicians, academics, and activists worked in a concerted fashion to convince the nation that economic planning and public investment outside of wartime was a threat to both prosperity and freedom.38 Their protestations largely fell on deaf ears until economic stagnation combined with inflation to create “stagflation.” With no other comprehensive solutions on hand, politicians starting with Jimmy Carter began to favor dismantling the last of the investment and coordination capacity of the state and a radical disengagement of the state from the economy.39 Ronald Reagan moved even more zealously in the same direction, while ramping up indiscriminate and wasteful government spending, in a policy resembling present-day communist Chinese stimulus spending, with his massive defense spending increases. Thus ended the last vestiges of the New Deal consensus that enabled the prior 30 years of mission mode.

The Korean and Vietnam Wars had also drawn time, money, and political capital away from America’s domestic political mission. Perhaps most importantly, the new and large American middle class, whose wealth and comfort would have come as a shock to an American in the 1930s, no longer saw America’s national mission as necessary.

Unfortunately, maintenance mode usually eventually leads to decline mode, in which basic investment is forgotten, and things start to fall apart. Nations never intentionally enter decline mode, and generally only come to terms with the fact they are in decline once it is too late to easily reverse it.

In decline mode, a nation begins deconstructing the companies, institutions, and state capacities it built while in mission mode. Governments begin cutting back on social services and investments in national infrastructure. This is done either through gratuitous privatization for privatization’s sake, or by defunding programs to kill them. The state’s capacity to execute what programs are left is also diminished. The fruits of mission mode are auctioned off or abandoned. People begin to expect worse results from the government, which in turn makes it easier to gut more programs, as angry voters vengefully elect anti-government politicians.

At first, companies begin pulling back from investing in physical assets and instead put their money into the financial casino. Many companies begin to consolidate, and smaller companies get bought out by large conglomerates — only to become stripped down into worse versions of themselves.

Nations rarely recover from decline mode by gradually moving back to maintenance mode. The problem is that the longer a nation lives in decline mode, the more elites, companies, and government agencies develop survival strategies and business models compatible with or dependent on decline. Elites who build their wealth during a period of mission-driven national growth can then live on that capital without necessarily investing heavily as the country slides into decline mode. In general, only the urgency and disruption of a national mission can break the web of dysfunctional and corrupt habits and relationships that keep a nation in decline.40

Today, the United States is not in mission or maintenance mode — America is in decline.41 As we’ll explain, jumping straight to mission mode is the way to get out of decline. The Mission for America is a political strategy, policy framework, and national business plan to do just that.

Only a president can call America to a mission — and ensure it’s accomplished

Nations are called to missions by leaders. In the U.S., given the structure of our system, that responsibility falls on a president. Most nations that have undertaken national missions since World War II have been democracies, with political parties or coalitions of parties pitching their nations on the missions in elections or from office, including Germany, France, the Nordic nations, Japan, South Korea, and many others.42 In some cases, the mission was pushed by a single leader above all, while in other cases a broad team of leaders presented it together. It should be possible for the Mission for America to be introduced by a coalition of leaders in office or running for office, including a president and congressional leaders. They could represent a single party, a new non-partisan movement, or a mix of leaders from different parties and independents. In the U.S. system, however, presidents or presidential candidates are the de facto leaders of political parties and movements, and they are the only figures who have the centrality to cut through the noise and speak audibly to the whole American people. Therefore, the role of pitching America on a mission likely must fall to a president and their team.

We call for the Mission for America to be pitched in the context of a presidential campaign. It is difficult for Americans to imagine this happening because it has never happened before in our history. In the two times we embarked on a national mission to transform and build up our economy (the Civil War and World War II), the mission was proposed by a president already in office, and both times it was in the context of war. It is unfortunate that we can’t point back to a moment in our history when a presidential candidate and their party or coalition proposed a national mission and then carried it out. But this is not an insurmountable obstacle, and we can look outside of the U.S. for evidence to show us why.

Internationally, numerous examples exist of countries that mobilized to build a new economy in peacetime, under democracy, when leaders proposed a national mission in a campaign or from office. After World War II, social democratic developmentalist parties won elections with resounding majorities all over Western Europe and many parts of East Asia and Latin America.43 These parties proposed sweeping programs of modernization and industrialization. By and large, they delivered immediate progress, and their populations rewarded them with additional terms in office that allowed them to make more dramatic transformations. In nearly all these cases, democracy proved its utility by allowing electorates to keep the pressure on the dominant party by flirting with others. In postwar Japan, for example, voters gave the Socialist Party one term in office early on, which impelled the dominant Liberal Democratic Party to refocus on delivering continuous economic progress for the population.44 Similar patterns can be found in most other rapidly industrializing postwar democracies.

Such democratic engagement is crucial because national economic development missions, like the Mission for America, require multiple political terms to implement. Hence, they must provide tangible and immediate benefits to voters so that they elect more leaders who support the mission as time goes on. The Mission for America is designed to provide clearly visible benefits to the entire nation in general, and to tens of millions of people directly, almost immediately, so that the president will gain seats instead of lose them in the first midterm elections. This strategy is vital for maintaining momentum and political backing to accomplish ambitious objectives.

And indeed, the Mission for America is a plan to make big things happen — modernizing old industries and creating new ones, building and repairing infrastructure, achieving technological breakthroughs — and making them happen as quickly as possible. A plan of this scale will require billions of dollars in public investment, coordination between many industries, the support of political leaders at all levels of government, and cooperation with America’s international allies.

While states and local governments have a huge role to play in the Mission for America, they are incapable of doing this mission on their own. There are simply too many states, each with unique interests and local needs, to cooperate on a mission this big. It is extremely unlikely that all 50 governors and a majority of all state legislatures will agree on a unified vision for the country. Even if they did, maintaining coordination and cooperation between 50 state governments for a decade would be impossible without federal leadership. States and local governments also don’t have the economic resources to marshal the necessary level of investment, as most operate on shoestring budgets and have constitutional bans on running deficits.45

The private sector is incapable and unwilling to carry out this type of mission on its own. Private industry has a natural tendency to chase short-term profits over long-term investment — even at the expense of their own future success.46 This short-sighted behavior has been encouraged by decades of American policy decisions and cultural norms. Court decisions such as Dodge vs Ford Motor Co. (1919) solidified the norm of shareholder supremacy and oriented corporate behavior around the short-term desires of corporate shareholders.47 Financial deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in dozens of new, esoteric financial mechanisms that promised significantly higher returns than traditional investment in physical assets.48 At its core, the private sector’s focus on immediate profits often overlooks the long-term investments necessary for national transformation.

Given these limitations, only the federal government has the scale, resources, and mandate to successfully initiate and lead a mission as ambitious as the Mission for America. Therefore, the Mission for America is a plan for a president and their administration to mobilize the federal government to accomplish a set of national missions corresponding to different challenges and sectors of the economy.

America has largely forgotten that presidents and the federal government can get big things done other than war. Other than wage wars, the biggest thing most people can remember a president doing was the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which simply expanded public healthcare programs that already existed and made deals with insurance companies to change some health insurance policies. Those expansions and many ACA policies were incredibly important for millions of people — for example, by barring insurance companies from denying care for preexisting conditions. But the ACA was tiny compared with the full-scale transformation of our economy that our double crisis demands of us. Since the ACA is regarded by many policy thinkers and politicians as the biggest thing a president could possibly achieve under modern circumstances, making the case that the Mission for America is possible is an uphill battle.

To understand what presidential leadership is capable of, we must look back to Franklin Roosevelt who inherited the Great Depression and took actions bold enough to overcome it. He approached it with a willingness to act audaciously and try anything. His schemes often included misguided policies and programs that backfired. However, voters backed him and his party in election after election because his biggest and most decisive actions worked astonishingly well to solve the economic crisis, raise living standards, and build wealth. When World War II came, FDR’s mission expanded to include mobilizing our economy to supply the U.S. and allied militaries with an overwhelming and unimaginable quantity of weapons and materials — all while building an entirely new, technologically advanced industrial economy that would provide prosperity and security for generations.

Some of President Roosevelt’s bold actions included:

Taking the U.S. currency off the gold standard — against the advice of nearly all his closest advisors — to allow expansionary lending and spending to get the economy growing again.49

Closing and recapitalizing the failing banking system, combined with a personal appeal via his famous radio “fireside chats” to the nation in which he asked the public to have faith that when it reopened, it would be worthy of their trust.50

Massively expanding the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), created as an emergency measure by Herbert Hoover, and turning into a permanent investment and coordination institution that would guide the U.S. economy through both the Depression and World War II.51

Directing the RFC, which became the largest corporation in the world, and other war-mobilization institutions that he created to fund and coordinate the creation of entirely new industries and vast new infrastructure and recruiting thousands of leaders from industry and finance to lead those efforts.52

Creating scores of other investment and coordination institutions, many as spin-offs of the RFC, and many of which live on today as public or private corporations and agencies such as the FDIC, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Export-Import Bank.53

Creating the Social Security system, which perhaps did more than any other single policy in American history to reduce poverty and increase prosperity.54

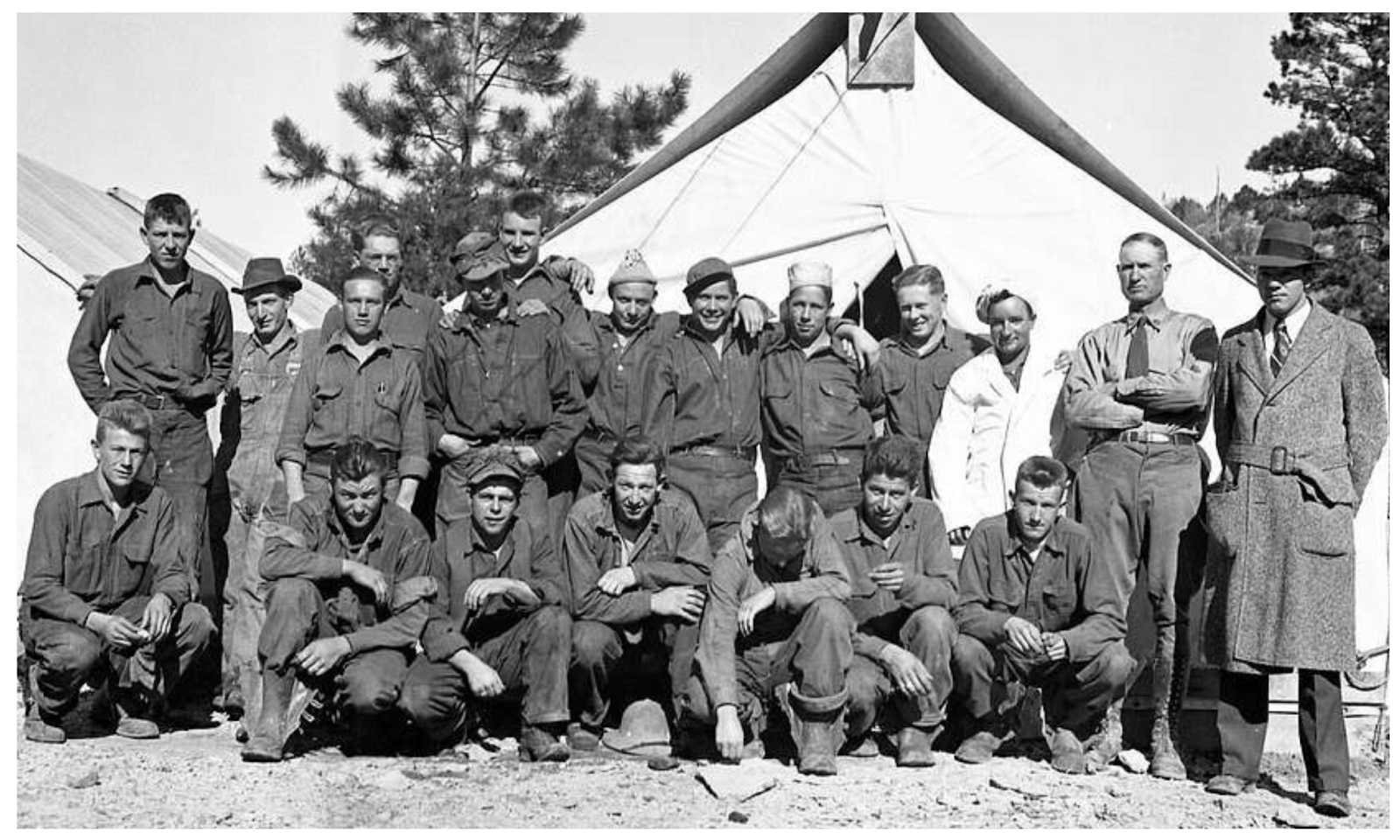

Creating the Civilian Conservation Corps (against the resistance of almost everyone in his cabinet and the military) that gave millions of unemployed and homeless people jobs that maintained or restored their employability, provided income to millions, and provided important investment and restoration for countless communities.55

Modernizing and scaling national infrastructure in projects that provided employment to millions and that accomplished feats as great as delivering electrification to virtually every American.56

By making those bold moves and many others, Roosevelt massively expanded the size of the U.S. economy and advanced it technologically to heights that would have looked like magic before his presidency. What he added to the U.S. economy and society formed the basis of the next 80 years of American global prosperity.

The Double Crisis

As mentioned, the Mission for America is designed as a response to dual crises that America and the world are facing:

The climate and environmental crisis, and

The economic and social crisis

Both threaten to radically intensify in the coming years. Only action on the scale of the Mission for America can resolve them, and they’re also part of what will make the Mission for America politically feasible as the disruption caused by the crises changes the bounds of public opinion.

Even if we didn’t have the economic crisis, the Mission for America would still be the best path to promote prosperity and stability for all Americans. Likewise, even if we didn’t have the environmental and global warming crisis, moving off of fossil fuels, “electrifying everything,” and ending waste and pollution would greatly improve quality of life for the whole world.

In history, many nations have undertaken transformations on an equivalent scale to the Mission for America proactively, without needing to be pushed by a crisis, but as it happens, we are facing these two crises now, and both have unique consequences and solutions in the United States.

The climate and environmental crisis

The world is already experiencing the consequences of global warming — and this will only intensify in the coming years. Extreme, prolonged, deadly heat, and catastrophic droughts, wildfires, floods, and other disasters are accelerating at unpredictable rates. The effects of climate change are unevenly distributed, and many densely populated regions will experience far greater warming than the global average. Some parts of the world will experience conditions fundamentally incompatible with human life.57 In the coming decades, millions of people will die from the effects of climate change, and hundreds of millions or even billions more will be displaced.58

Several factors not often considered may already be causing global warming to accelerate exponentially. Climate feedback loops happen when warming accelerates the release of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere and oceans, which in turn causes greater warming, which leads then to faster release of greenhouse gasses, and so on. There are many known (and probably still unknown) kinds of climate feedback loops, and here are just a few:

Ice-albedo feedback: When ice melts, it exposes surfaces like water or land underneath. Because these surfaces are darker than ice, they absorb more sunlight and heat, leading to more melting and overall greater global warming.59

Permafrost thawing: As global temperatures rise, permafrost thaws, releasing stored methane and carbon dioxide, further warming the atmosphere.60

Water-vapor feedback: Warmer temperatures increase evaporation, leading to more water vapor in the atmosphere. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas, so this increases warming.61

Ocean methane: When ocean temperatures rise, methane hydrates deep in the ocean can destabilize and release methane.62

Paradoxically, another factor contributing to accelerated warming is the reduction in fossil-fuel use and the shift to cleaner alternatives. Burning fossil fuels like coal and diesel releases aerosol particles which temporarily cool Earth by reflecting sunlight away.63 Unlike long-lasting greenhouse gasses such as carbon dioxide, these aerosols have a short-term cooling effect because they settle back to the earth over a few years. As we transition to renewable energy, the long-term warming impact of accumulated CO2 persists, while the temporary cooling from aerosols quickly dissipates.64

To be clear, continuing to burn fossil fuels so that aerosols continue to have their cooling effect is not an option. Burning fossil fuels releases CO2 which increases global temperatures in effect permanently every day that we continue. The warming effect of CO2 added to the atmosphere is cumulative, which means that the longer we burn fossil fuels, the hotter the planet will get. And the limited cooling effect of aerosols cannot protect us from the unlimited warming effects of releasing more CO2 into the atmosphere.65

Hence, as we reduce how much fossil fuels we are burning, and as we switch from dirtier to cleaner fuels (i.e., fuels that release fewer aerosols), we will experience an immediate increase in global temperatures. Some scientists estimate that the cooling effect of the aerosols, which we will lose, may be as great as several tenths of a degree.66 This alone will push the earth to the brink of 1.5 oC above pre-industrial times.

The year 2023 was a stark indicator of this trend, being the hottest year on record and likely the warmest in hundreds of thousands of years.67 With a global temperature 1.35 °C higher than pre-industrial times, it approached the 1.5°C threshold set by the international community. While global and local temperatures fluctuate due to various factors, making 2023 potentially an anomaly, it’s more likely a sign of exponential global warming acceleration. If this trend continues, we may face more severe consequences of global warming in the next few years, including:

Mass death from heat in areas that are hot, densely populated, and low-income and therefore lacking in infrastructure to protect people from extreme warming.68

More frequent and powerful storms that will sometimes hit major cities unequipped to deal with high winds and flooding.69

Uncontrollable wildfires that begin to destroy densely populated areas.70

Devastating flooding in population centers unequipped to deal with it.71

Serious droughts that threaten agricultural and even drinking water supplies.72

The disruption of food supplies from failures in agriculture and fishing.73

And those are just a handful of the possible catastrophic consequences we face.

Aside from climate change, the environmental crisis is also the result of industrial pollution. This harms millions of people and affects human and animal biology in ways we are only starting to understand.74 Countless toxins are now found in drinking water, food, human bodies, and even breast milk. It is close to impossible to study the effects of these low-level toxins on humans because it is unethical to construct experiments where people are subjected to them. Nevertheless, it is known that many toxins humans are exposed to cause harm at any concentration. Most people have been conditioned to believe that a high level of daily pollution is the inevitable by-product of living in an industrial society and often don’t even recognize the amount of pollution they are exposed to on a daily basis. The reality is, however, that millions of people die prematurely worldwide because industry is polluting the air they breathe.75

Much more can be said about the destruction of the natural environment by human activity that is beyond the scope of this introduction.

The economic crisis

For decades, the United States has been dismantling and exporting its means of making a living in a process that has enriched the professional, managerial, and owning classes while eroding the wealth and quality of life of approximately the bottom 80% of income earners.76 In response to this crisis, our political system has supplied two kinds of leaders: “decline managers,” who seek merely to slow the rate of our demise, and “destroyers,” who erode state capacity while selling off national assets and resources to the lowest bidders.

As our government changed hands back and forth between decline managers and destroyers, inflation-adjusted wages for most workers have fallen or remained flat, public services and infrastructure have atrophied, and the costs of housing, healthcare, and education have skyrocketed.77 This has led to a sharp loss of trust in our national institutions and finally has culminated in a full-blown political crisis. Today, the threat of a democracy-ending coup, supported by a large minority of the population, is a reality.78

On top of this gradual systemic unraveling, the U.S. economy is plagued by periodic financial collapses that are an unavoidable consequence of our economic system and its institutional framework. With every crisis, the destroyers allow the decline managers to take the lead in working out a bailout of the system — and then spend the following years relentlessly attacking them for it. In the past two crises — the 2009 financial collapse and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic — decline managers created trillions of dollars worth of new money, in the form of debt, with which to bail out companies, investors, and even, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, workers directly.

In both of those recent crashes, financial leaders on Wall Street and in the government believed that a collapse as devastating as the Great Depression would come if the federal government did not immediately bail out failing banks and other private financial institutions. They were probably right. But the creation of trillions of dollars of debt to bail out big banks during the 2009 financial collapse — while many ordinary Americans lost their homes — left citizens and politicians from both parties disillusioned and embittered. Thus, more than a decade later during the COVID-19 pandemic, the government adopted a more inclusive approach that provided financial support to small businesses and workers, in addition to big corporations and financial institutions.

In hindsight, leaders in both parties hold serious qualms about unrestrained bailouts. Many Democratic and Republican members of Congress feel they were rushed into approving reckless bailouts by Wall Street CEOs and federal officials. When the U.S. inevitably encounters another financial collapse, bailouts may not come quickly and freely enough to prevent a major financial catastrophe. This would not be wholly inappropriate. Rushed bailouts do nothing to correct the long-term fragility of our financial system. If the U.S. finds itself in the depths of a financial crisis on the scale of the Great Depression, leaders and the public may be willing to look for long-term solutions.

Beyond the immediate economic challenges, there are deeper systemic issues at play. Like the climate crisis, the economic crisis contains self-reinforcing feedback loops. As the state fails to deliver economic security, angry voters often elect anti-state leaders and parties that only make matters worse. For decades, the Republican party has practiced an anti-government electoral strategy, and has governed in a way that generally reduces the stability and capacity of the federal and state governments, for example by stigmatizing public service and expanding the national debt without restraint. The Democratic party often competes with the Republicans by promising anti-government policies of its own and has typically worked to reduce the debt after Republican presidencies that blew it up, making cuts to public services and social programs along the way.

Parallel to these political and economic feedback loops, another feedback loop looms at an uncertain distance. Artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics could begin replacing very large numbers of workers very soon.79 In particular, AI will have a disproportionate impact on “knowledge workers” — a fuzzy and questionably named category.80 Once AI can passably simulate humans working at a computer, it will be able to quickly replace humans with virtually no physical investment required. Moreover, it will come with many advantages over humans. For example, a single AI presence will be able to replace many individual workers at once, eliminating clumsy interpersonal communication, rivalries, and work far more efficiently and powerfully. Mass replacement could begin for jobs such as call center workers, paralegals, bookkeepers, copywriters, and many others when innovative companies dramatically cut their costs and prices with AI, leading competitors to follow or die. The downward feedback loop then kicks in as demand is depressed by those mass layoffs, leading to either a perception or a reality of depressed demand. That depression then leads other employers to lay off workers and could speed the adoption of AI to replace workers across new fields. In this feedback loop, layoffs drive layoffs.

One critical challenge the Mission for America would face if it was launched under present-day circumstances would be a severe shortage of labor.81 On the other hand, it would be the perfect solution to a crisis of unemployment caused by financial crisis, automation, or a combination of both. When societies fall into unemployment spirals, as most industrial countries did during the Great Depression, the only way to decisively turn that around is to create programs for mass employment in productive and necessary work. The New Deal mainly mobilized unemployed workers in make-work, consistent with the prescription of economist John Maynard Keynes that the government could “pay people to dig holes in the ground and then fill them up” — and that such policies would, on a sufficient scale, jumpstart demand and get a depressed economy rolling again.82 Though it helped to stem the free fall of the depression, those kinds of policies never fully restored confidence and growth in the economy. Only the mobilization around World War II that created jobs making actually valuable and necessary goods could do that. If the economy faces a free fall in employment, the Mission for America is the perfect solution to that crisis because it has the power to employ everyone in productive, lucrative work by building the industries that we need domestically and that the whole world needs at large.

A small but growing number of economists and other experts predict that the exponentially increasing abilities of artificial intelligence and robots will create a situation in which the vast majority of — if not all — knowledge jobs will be more economically done by machines.83 If this does turn out to be the case, the path from the kind of economy we have today to an economy where virtually all jobs are automated and humans still have economic security will not be automatic. The Mission for America is designed so that it can be the bridge to that fully automated society. Though it doesn’t spell out the final steps, it is a program that can provide full employment to a rapidly automating society — by employing many tens of millions of people in the effort to build the clean industries and infrastructure that must be built immediately. That physical work — which includes both high- and low-skill jobs — will not be automated by robots anytime soon. By providing the institutions, financing, training, and coordination to create virtually unlimited profitable jobs, the Mission for America would maintain employment through a period of rapid automation that would otherwise be economically devastating. In this case, around the time that the Mission for America is accomplishing its goals, another mobilization and transformation will be needed to establish an automated society in which people can live securely and in control of the means of making a living. This would be the most exciting and profound transformation humanity has ever experienced. At New Consensus, we hope to work on provisional plans for such a transformation in the near future.

To address these multifaceted challenges, the Mission for America includes a comprehensive solution that aims to provide permanent economic and financial stability for the U.S. economy. This will be achieved by adding much-

needed financial institutions and industries to our society, creating a robust framework to support the transition to a rapidly changing and economically secure future.

Feedback loops between the two crises

Each of the twin crises have effects that intensify the other. For example, climate change causes droughts and natural disasters that threaten the global supply chain — inevitably causing rising prices and shortages of key goods.84 Rising temperatures will accelerate climate migration from developing countries, draining developing countries of their most talented workers and placing unpredictable strains on developed countries’ immigration systems.85 Concurrently, the more that national economies are burdened by the climate crisis, the fewer resources they will have to reduce emissions and adapt to a warming climate in the short run.

Recognizing these intertwined crises and their reinforcing feedback loops, the Mission for America proposes a comprehensive mobilization led by the federal government and a proactive president. This plan aims to not only mitigate the individual impacts of climate change and economic instability but also to break the cycle of each crisis exacerbating the other. By simultaneously tackling environmental challenges and bolstering economic resilience, the Mission for America seeks to transform these feedback loops from negative to positive, driving progress in both areas.

What it will take to solve the twin crises

What makes solving these kinds of self-reinforcing, spiraling crises difficult is that small, measured steps are insufficient. Overcoming an accelerating crisis requires an effort large and powerful enough to not only counter the downward fall but also create lift in a positive direction. It is unsustainable, both financially and politically, for a society in a downward spiral to merely slow decline. Decline management is expensive and doesn’t result in new sources of revenue from growth. It is much more expensive to spend trillions of dollars over the course of decades making decline less painful than it is to spend billions in a short period of time to reverse it. Perhaps most importantly, voters who don’t experience growth and progress will ultimately lose faith in decline managers and begin to look for alternatives. Too often, these alternatives are anti-democratic despots looking to divide citizens and profit from decline. Liberal democracies rarely survive in decline mode for very long. Leaders committed to liberal democracy must pull them out of decline before it is too late.86

In other words, solving these enormous, intractable, and intensifying crises requires a sort of “national escape velocity.” The Mission for America is designed to achieve that, by organizing effort of sufficient scale and impact, and by front-loading the mission with enough tangible progress for voters that they will give it a chance to continue.

This is why the Mission for America is not only a policy framework but also a political strategy for a president and a national business plan for corporate and small-business America. Its plans would lead very quickly to more jobs and higher wages by providing millions of high-wage “shovel-ready” jobs and training. It ensures that those expenditures will be afforded by large increases in national income from lucrative investments that will take some time to yield results.

Assuming current political, economic, and climate trends persist, the Mission for America is designed to be an economically, technologically and politically feasible plan to overhaul the entire economy. Continuing America’s three-hundred-year national lucky streak, we are blessed with the exact combination of resources, labor, capital, and institutions that will allow us to solve the double crisis — if only we can muster the leadership to act proactively and wisely.

How a mission to solve the double crisis could unite America

America’s intense political polarization makes it difficult for some to imagine how a president could unite America behind a national mission. The American electorate has fractured into two distinct political tribes, and the divide between them gets larger every year. Although this divide has its roots in the middle of the 20th century, it has been worsened by the rise of social media and conspiracy-driven news sources. Intensely partisan talk radio, cable TV, and internet-based enterprises have created their own information ecosystem that pushes conspiracy theories with an anti-government, libertarian, and racist bias. The resulting social tensions reached a breaking point in the aftermath of the 2020 election, in which a large portion of the American population refused to accept the results — and a particularly emboldened few attempted a coup.

If Americans can’t come to a consensus on basic facts, and if some reject liberal democracy altogether, how can we claim that a president could build support for something as big as the Mission for America? We recognize that political polarization will pose a challenge to the Mission for America president. Yet, for the four reasons below, we’re confident that a capable and determined president can successfully call our divided country to this national mission:

A well-designed national mission can appeal to the interests of voters across the political spectrum.

America’s institutions can be reformed so that our proposals will need only a simple majority to pass.

A national mission that delivers immediate and noticeable improvements to quality of life will create a lasting political coalition.

As the dual crisis intensifies, the public will favor sincere and practical solutions over conspiracy theories if they are presented coherently by leaders determined to and capable of following through.

The Mission for America is designed to appeal deeply to both of America’s political tribes. It calls for an economic renewal that would make good on Donald Trump’s call to “Make America Great Again” — in that it would provide prosperity and security for all and restore America to its former position as a net-exporting economy that sets the pace for the world. It proposes to achieve that through a massive economic mobilization to replace our greenhouse-gas emitting industry, infrastructure, vehicles, and other equipment and machines with clean alternatives — and to establish the U.S. as the leading exporter of the most valuable goods and services the world will need to get off fossil fuels, to enable a faster global transition. We’re under no illusion that America will easily unite around both of these goals as one happy family. But we believe it contains the ingredients an innovative presidential candidate could use to build a movement beyond their party’s traditional base.

Given present political realities, the Mission for America president will almost certainly fail to win over the opposition party to join in making the mission a success. Given current senate rules, a supermajority of 60 votes is needed to pass comprehensive legislation, thanks to the filibuster.87 The Senate filibuster is a procedural rule in the Senate that allows a single senator to extend debate on a piece of legislation until a supermajority of 60 senators votes to end debate. It is exceptionally rare in modern America for a party to have 60 or more seats in the Senate. Democrats and Republicans have both occasionally used an obscure process known as “budget reconciliation” to bypass the filibuster. However, the procedure applies only to budget-related bills that reduce the deficit, which will limit its usefulness in the Mission for America.

Abolishing the filibuster can be done with only a simple majority in Congress.88 This rule change will allow for the passage of the Mission for America’s policy proposals with a simple majority, sidestepping the need for overwhelming bipartisan consensus or the confusing budget reconciliation process. The House of Representatives was also once hamstrung by a rule similar to the filibuster, but was abolished in 1890 by Republican House Speaker, Representative Thomas Brackett Reed Jr. of Maine.89 It is time for this to happen in the Senate.

Ending the filibuster is already a mainstream idea within the Democratic Party and wider policy circles.90 Although an attempt in 2021 fell short by a narrow margin, the political landscape has since evolved. The two senators most responsible for preventing filibuster reform — Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Krysten Sinema (I-AZ) — have either announced their retirement or left the Democratic Party.91 The next Democratic majority will very likely be open to abolish the filibuster and begin passing ambitious economic legislation on day one.